Memetic

Memetic is an open source property graph schema and query language. It defines graph schemas, patterns for how vertices and edges (which Memetic calls entities and links, respectively) function as well a querying syntax. It is designed to be easy to use, yet powerful. A property graph engine that supports Memetic allows for complex schema modeling of nodes. Graphyne is an example of a property graph engine that supports Memetic. In fact, Memetic as created in order to serve as a schema language for Graphyne and its documentation shows the use of Memetic in action.

The Trinity: Metamemes, Memes and Entities

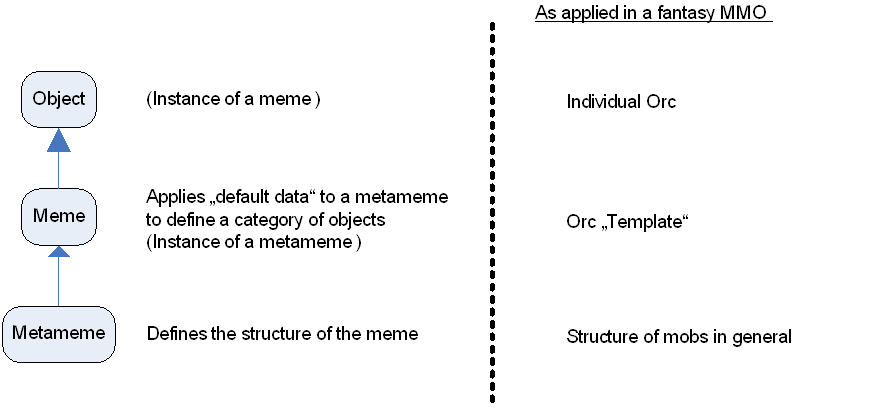

The deep core of Memetic is a trinity of the meme, metameme and entity. At a low level, it is a way of defining and manipulating graph entities, links, the models from which they are made (memes) and the meta-models with which those models are defined (metamemes). Memes and Metamemes are known collectively as templates and are defined via xml. Entities exist only at runtime, in the graph engine. There is a fourth element, the link. These play a subservient role at runtime and are used to navigate relationships.

The Short Explanation

If you are familiar with programming, using an object oriented language, then entities, memes and metamemes can be understood to correspond roughly as follows:

- Metameme = Abstract Class, or Interface

- Meme = Class

- Entity = Class instance

The Longer Explanation

Let’s start by examining entities and links. This is the conventional part of the graph and the part shared by all property graphs. Entities are the nodes in an interconnected cloud of “things”. The links are the ties between them. Let’s consider a bicycle as a Memetic graph. Its major components are all entities, the frame, handlebars, wheels, etc., and they are linked together.

Our bicycle is not the only of its kind. Unless it is a hand-built, boutique bicycle, it was likely mass produced from a specification on paper using whatever components its product manager decided on. These components are delivered via a modern supply chain and might not have even been produced until the bicycle manufacturer ordered them from the component manufacturer’s catalog. This specification and the specifications of the component parts in turn are known in Memetic as memes. Meme is a term created by Richard Dawkins to define a unit of information and that is the role that it plays in Memetic. It is the designer’s workhorse and may define an entity of some sorts, it may define a change of state for that entity, or it may define the reporting of the state of an entity to a client.

Then the bicycle designer specifies the components, she chooses a particular model of brake. The Acme XYZ hydraulic disc brake is a type of speed arresting device, specifically a kind of bicycle disc brake and more specifically a kind of hydraulic disc brake. These abstractions are that Memetic calls metamemes metameme. Metamemes defines the structure of memes.

Memes and metamemes provide a “clean” way of organizing and designing objects. For example, someone designing a fantasy MMO might want to have orcs. An individual orc would be an object. That orc would be created as needed from a template; a model of an orc. We call this a meme. A metameme is the definition of the structure of a meme; a generic “mob” in this case. Memetic’ metamemes and memes are intended to allow designers to design their own objects and data structures without writing any code. They are also intended to lend portability, allowing re-use and trade of structures and concepts.

Schemas

Memetic schemas can be defined in XML. This might seem old fashioned and passé in a world of JSON. This has the advantage however of being able to use the xml schema definition to enforce semantic rules in the editor and thereby making it easier for the property graph engine to parse. It is not mandatory that schemas are always defined in XML. The Graphyne property graph database can consume XML Memetic schemas, but also has a generic meme hardcoded in.

Metamemes

Metamemes themselves have a very simple structure and contain only three types of information: references to metamemes that are to be enhanced, references to metamemes that are to be extended and properties. Metamemes are definable as graphs for human readability and design purposes.

Meta Meme Properties

A metameme may define any number of properties, from zero to infinity. Each one of these definitions includes the name of the property and the type. The type is one of the following: string, list, integer, boolean, decimal.

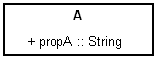

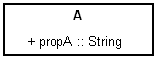

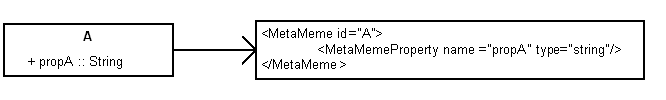

The metameme in the figure below defines a single string property, propA. A metameme in a graph is a box with a horizontal line through it. Above the line is the name of the metameme; “A” in this case. Below the line are the property definitions. The format of a property definition is the name of the property separated from the type by a double colon (“::”).

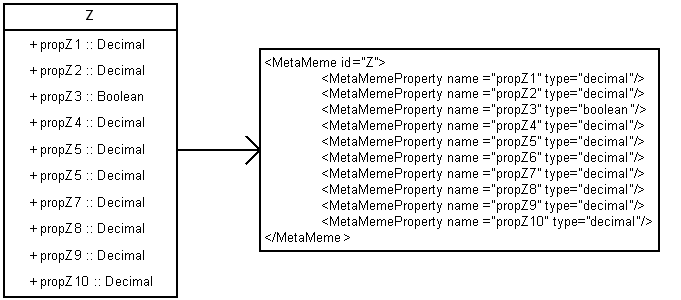

The property definition region is expanded and contracted as needed. On the left side of the figure below, the metameme defines no properties. The one on the right defines many.

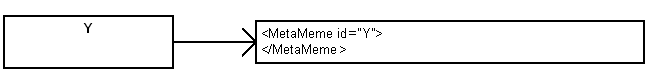

The XML version of such simple metamemes is also very simple. The name of the metameme is defined in the id attribute. The property definitions are defined in MetaMemeProperty elements, inside the parent MetaMeme element.

Metameme Y in the figure below is the simplest possible metameme and is in fact empty. Only the id is defined.

Metameme A in the figure below defines a single string property, propA.

Metameme Z in the figure below defines ten properties. Most are decimal, though one is a Boolean.

Member Metamemes

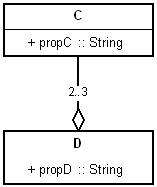

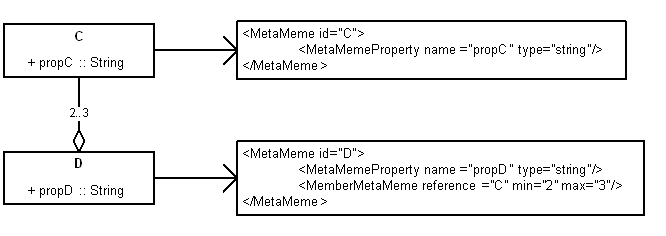

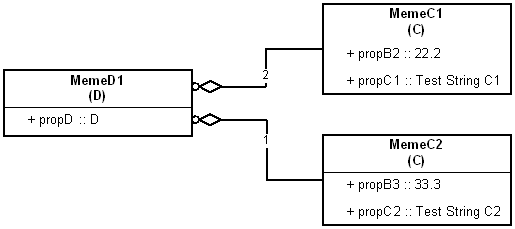

Metamemes may also define a hierarchal nesting of other metamemes within their structure. These are child metamemes called “member metamemes”. Strictly speaking, they are “Member Declarations”, just as metameme properties are really declarations of properties for child memes and not actually properties themselves. Metameme D in the figure below has 2 to 3 instances of metameme C as members.

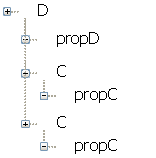

The structure of any meme created from D (called a child meme) would look like the figure below:

In XML form, member metamemes are defined in the MemberMetaMeme element. MemberMetaMeme may occur 0 to n times and MemberMetaMeme always follow the MetaMemeProperty elements. See the figure below.

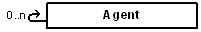

A metameme may have itself in a member declaration. This allows recursive, nested structures. The Agent metameme does precisely this. Because agents may have agents as members, inventory systems become trivial to implement and complex assemblies are possible. Recursive membership uses a slightly different graph connection compared to normal membership declarations. It curls back on itself and drops the starting diamond to save space (see the figure below). It is also possible to use a normal membership connector in the graph. There is no specific recursion element in the XML schema. It is simply a normal MemberMetaMeme with the value of the reference attribute being the same as the id attribute in the parent MetaMeme element. You can save yourself a lot of grief by never allowing a minimum cardinality greater than zero. Memes that have themselves as members are invalid as this would cause infinite recursion. Having a positive maximum cardinality simply allows entities to have entities of the same type as children at runtime.

MetaMeme Extensions

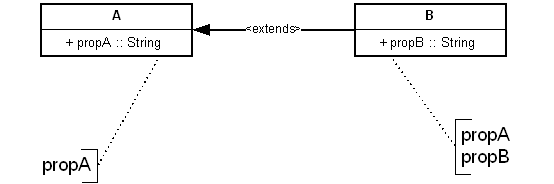

A metameme may extend other metamemes. This works similarly to class inheritance in object oriented programming languages and along with enhancement is one of the most important tools available to the designer. When a metameme extends another, the new metameme inherits all of the properties and member metameme hierarchies of the old metameme, in addition to anything that it itself adds. Metameme B in the figure below extends metameme A. Metameme A defines a single string property, propA. Metameme B defines a single string property, propB and inherits propA from metameme A.

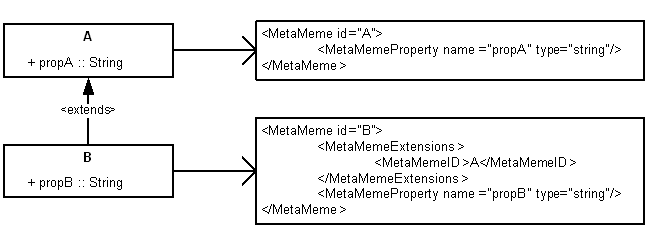

In the XML schema, the MetaMeme element has a single optional MetaMemeExtensions element. MetaMemeExtensions has one or more MetaMemeID elements that declare what metamemes are being extended. See the figure below.

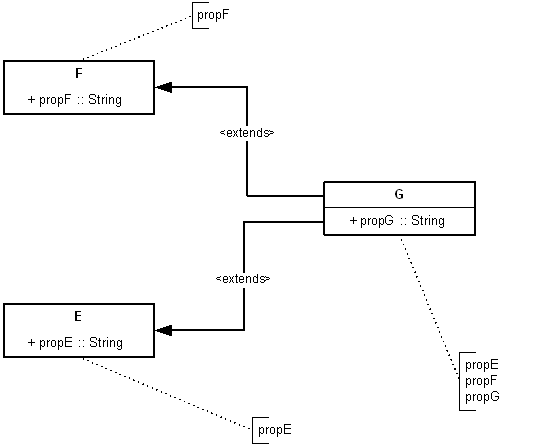

Multiple inheritance is possible with metamemes. A metameme may extend an unlimited number of other metamemes. Metameme G in the figure below extends both F and E; taking on their property definitions as well as its own.

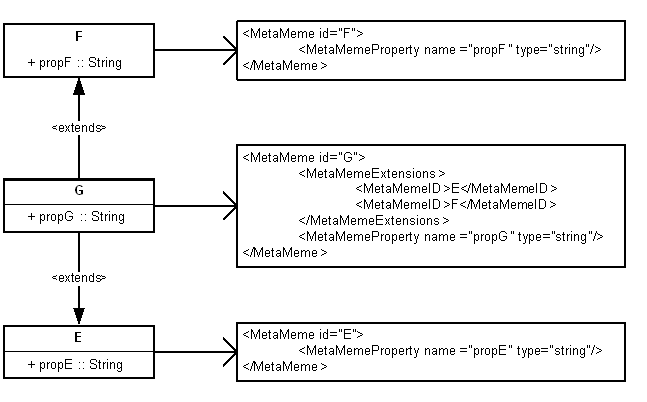

The figure below shows the XML schema form of E, F and G

Memes

Though they can be quite sophisticated, at their most basic level, memes are even simpler animals than metamemes. There are only three elements in the XML exchange schema (MemeProperty, MemberMeme and Meme) and only two diagram blocks. Essentially, it metaphorically “fills out the form” defined by the metameme. As such, a meme is always a “child” of a metameme. A shorthand way of referring to the parent metameme is to call it the meme’s “type”. A basic meme only needs to keep track of three types of information: a declaration of the metameme it is being constructed against, the values of the properties defined in the metameme and the paths of any member memes.

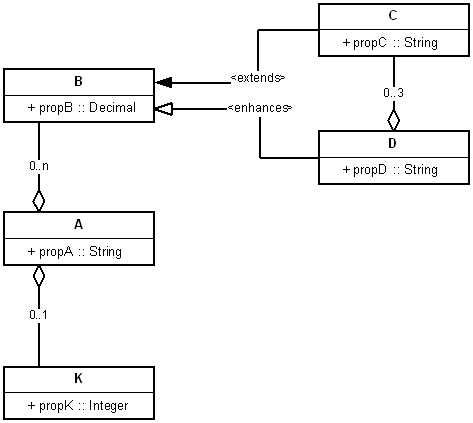

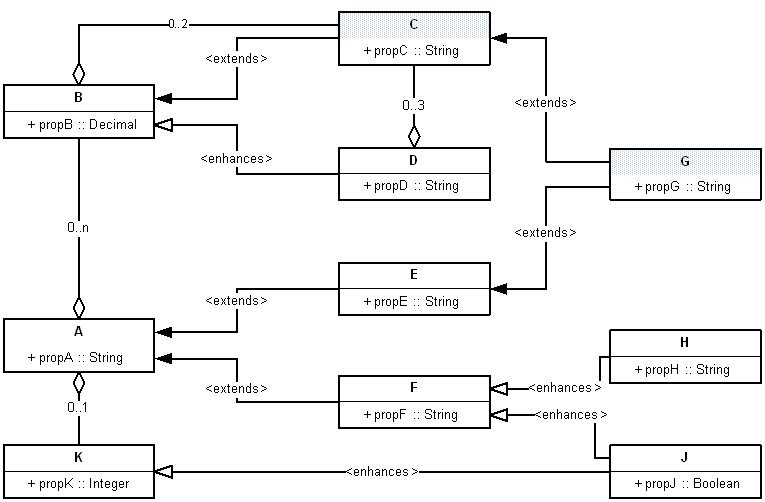

Metamemes A, B, C, D and K in the figure below are a subset the metamemes used in regression testing of the Graphyne graph database. Metameme A has two optional member metamemes, B and K. This means that any child meme of type A may also have optional member memes that are children on B and K. Metameme B is enhanced by D and inherits its properties; including C as a member metameme. Metameme C extends B, so in effect, B is recursive. It should be noted that had the minimum cardinality for C’s membership in D been non-zero, the recursion would be infinite and great care should be taken with membership recursion.

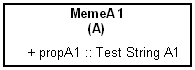

It is possible to construct memes of varying complexity based on metameme A. The simplest possible version in the figure below leaves out the optional members B and K and leaves out all properties. All properties defined in a metameme inherently have a 0..1 cardinality. This means that they are always optional and can never occur more than once. It has only its ID, declaration of the metameme used and the single property defined by MetaMeme A. The format is the same as in metamemes, with the name in the top panel and the properties in the lower panel.

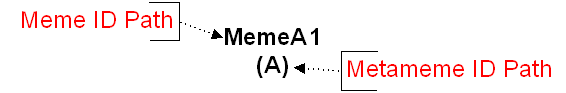

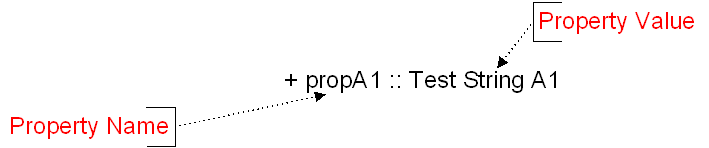

The top panel has two lines in the figure below. The upper line defines the path ID of the meme so that it can be referenced by other memes. The lower line (the part inside the parentheses) refers to the parent metameme; in this case metameme A.

Each property on the properties pane starts with a “+” to indicate a new property, then the name of the property, followed by a double colon (“::”) and finally the value of the property. There is no need to explicitly declare the data type as that is implicitly inferred from the metameme’s property declaration of the same name.

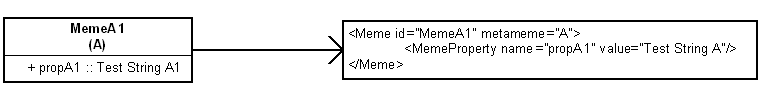

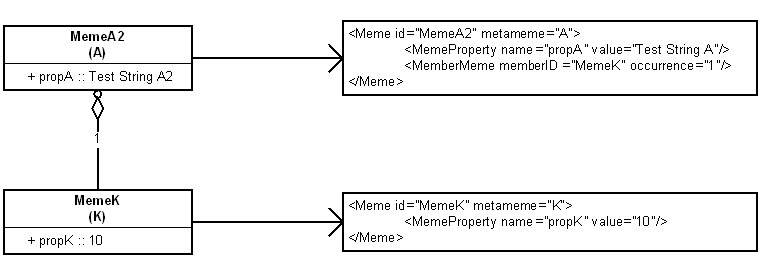

In the XML schema version of the meme, the path ID and parent metameme path ID are attributes in the Meme element. Each property element has two attributes, name and value. See the figure below.

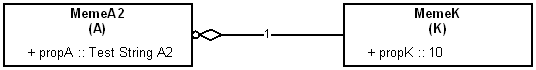

The indicator for membership in memes is similar to that of metamemes. The shape of the composition line differs slightly, with the start meme anchor having a circle before the diamond.

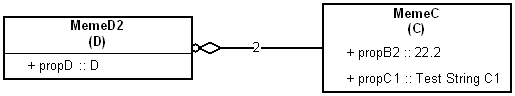

Another critical difference between meme membership and metameme membership is in how “cardinality” is handled. The cardinality on metameme membership defines a minimum and maximum membership, called occurrence. Meme cardinality defines absolute membership occurrence. Referring back to our previous example, we see that metameme D has metameme C as a member with a 0..3 cardinality. Therefore any meme created from D can have optional member memes created from C; but no more than three of them. In the examples in the figures below, there is a MemeD1 and a MemeD2 meme created from metameme D. As MemeD1 has three children and MemeD2 has two, both are valid. In the first case, the two children, MemeC1 and MemeC2, are two distinct memes of the same type; meaning that they are created from the same metameme. The occurrence of MemeC1is 2 and for MemeC2 is 1. So MemeD2 has three member memes, composed of two distinct types. In the second case, there is a single distinct meme, MemeC, with an occurrence of 2. When the occurrence of a distinct member meme is greater than one, each of these members is known as a discrete member. When the occurrence of a distinct member meme is greater than one, this is known as a stacked member. Virtual world designers would use stacked members to create item stacks; hence the name. Hence, MemeC1 is a stacked member and MemeC2 is a discrete member. MemeD1 and MemeD2 are also distinct memes of the same type.

In the XML schema of the meme in the figure below, the MemberMeme element has two attributes: memberID and occurrence. memberID refers to the path ID of the distinct member meme. occurrence refers to the occurrence count of the member meme.

Metameme and Meme Enhancements

Enhancement is an advanced feature of memes and metamemes. This is essentially a “sort of reverse extension”. It allows a meme to inject its properties and member into another, like a virus. This is especially useful in cases where the designer wishes to add properties to meme, or set of memes, but does not wish to, or can’t modify the root metamemes from which everything is derived. This may occur when external libraries of memes and metamemes are being used.

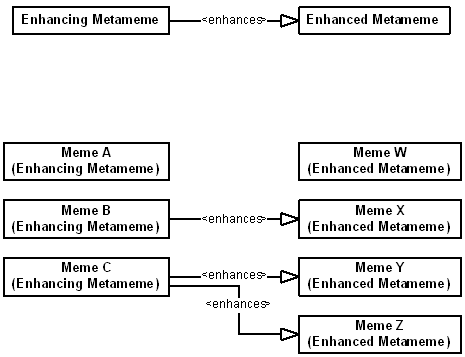

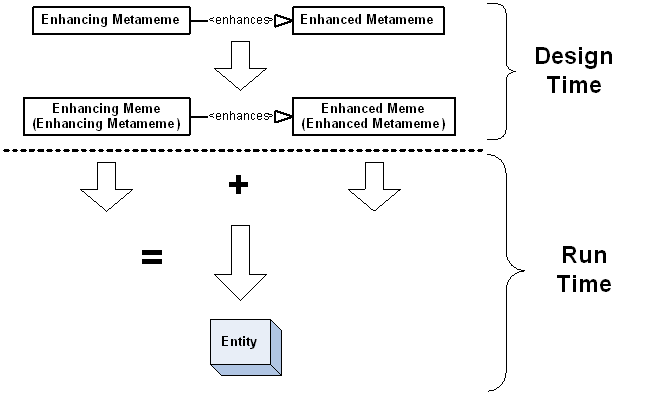

Aside from the direction of property and member inheritance; there is a critical difference between extension and enhancement. Enhancement is not strictly a metameme level modification, but a meme level modification that requires intent to be declared in the metameme. If A extends B, then A essentially takes on everything from B. All child memes of A have access to the property definitions, member definitions and non-overridden attribute settings from B. Nothing more needs to be done. When one metameme enhances another; it is merely the first step. It allows child memes of the enhancing metameme to enhance child memes of the enhanced metameme.

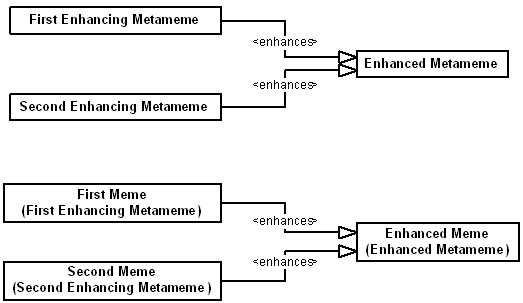

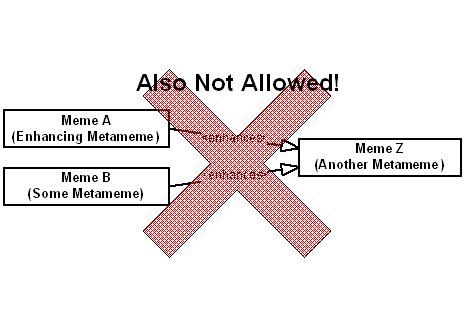

A meme may enhance any memes that are children of metamemes enhanced by its parent metameme in the figure above. As with extension, a metameme may enhance any number of other metamemes. A meme may enhance any number of other memes, as long as its parent metameme enhances their parent metamemes. Any of the memes that are children of the metameme Enhancing Metameme may enhance any of the children of Enhanced Metameme. Meme B enhances Meme X. Meme C enhances both Meme Y and Meme Z. Just because the parent metameme is involved in an enhancement, does not mean that the child meme must also participate. It is perfectly valid for Meme A not to enhance anything and for Meme W not to be enhanced by anything. Enhancement on the metameme level is merely a prerequisite for enhancement on the meme level and signals intent by the designer.

In the case of both enhancements and extensions, the merging of templates is applied one level higher than it is defined. With extensions, it is defined at the metameme level and the full set of properties and members from both the parent metamemes and any that it extends is available when working on the meme. Enhancement is happens at the meme level and is only applied at runtime when creating entities.

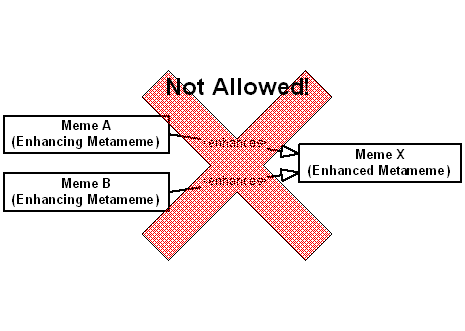

A meme may not be enhanced by two other memes of the same type.

Just as a metameme or meme may enhance any number of other memes/metamemes, they may in turn be enhanced by any number of other memes and metamemes. Just to be clear, only memes can enhance memes and only metamemes can enhance metamemes.

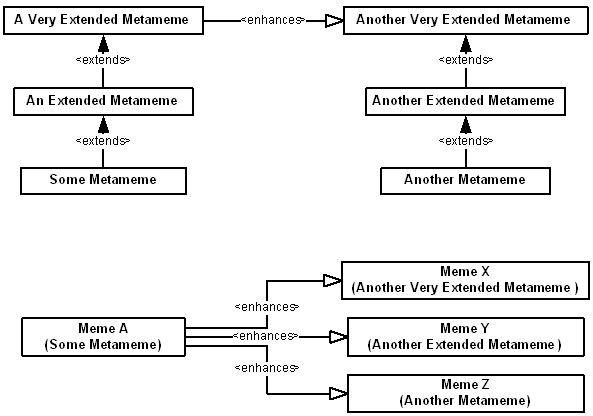

Enhancement lists at the metameme level are inherited through extension. If a metameme extends another, any child meme of any metameme that extends it may enhance and child meme of any metameme that extended the enhanced metameme. In the example below, Some Metameme is two extensions removed from A Very Extended Metameme, yet it inherits the enhancement of Another Very Extended Metameme. Likewise, any metamemes that extend inherit the target enhancement. As is shown in the example in XXX, it is valid for Meme A to enhance Meme X, Meme Y and Meme Z.

It should be noted that the prohibition on multiple enhancements from the same meme type involves the whole extension chain. Because Some Metameme extends An Extended Metameme, Meme B and Meme A may both enhance Meme Z; but because belong to the same family and only one of the two would be allowed to enhance Meme Z.

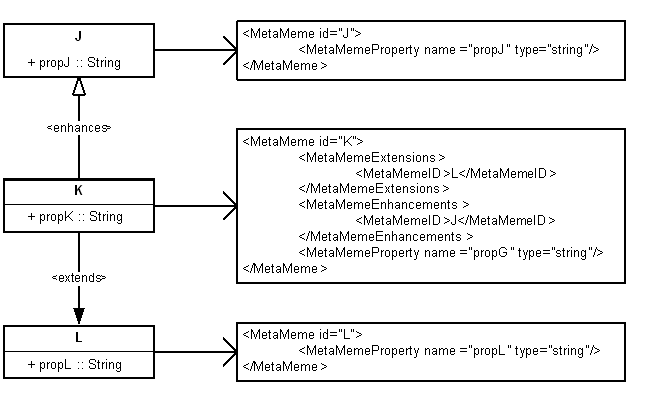

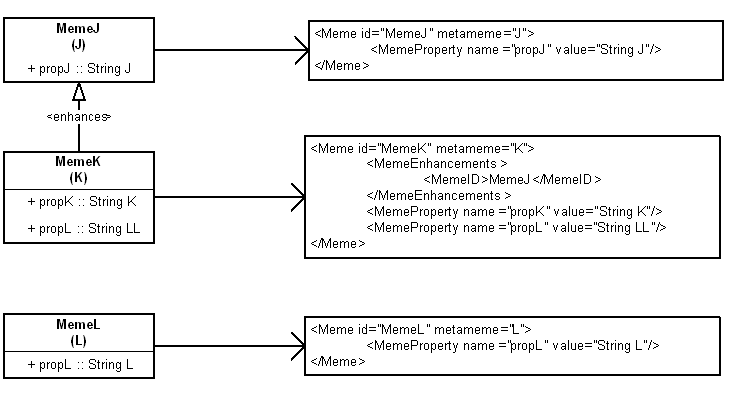

The figure below shows an example set of enhancements and the resultant entities. Metameme K extends metameme L and enhances metameme J. Each of the three metamemes has a single string property definition. The memes MemeL, MemeK and MemeJ are children of L, K and J respectively. Because K extends L, MemeK may also have propL in addition to propK; which it does. Note that MemeK and MemeL have different values for propL. Because K enhances J, MemeK is allowed to enhance MemeJ; which it does. If a metameme simultaneously extends one, while enhancing another, the enhanced metameme will also inherit the extension.

- Any entity created from MemeL has a property propL with a value “String L”.

- Any entity created from MemeK has a property propL with a value “String L” and a property propK with a value “String K”.

- Any entity created from MemeJ has a property propJ with a value “String J” in addition to MemeK’s properties, propL and propK with the values “String LL” and “String K” respectively.

The figure below shows the XML exchange format form of metamemes J, K and L

The figure below shows the XML exchange format form of memes MemeJ, MemeK and MemeL

Exclusive Membership (Switch)

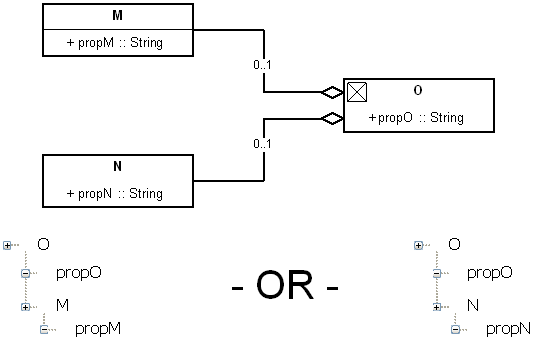

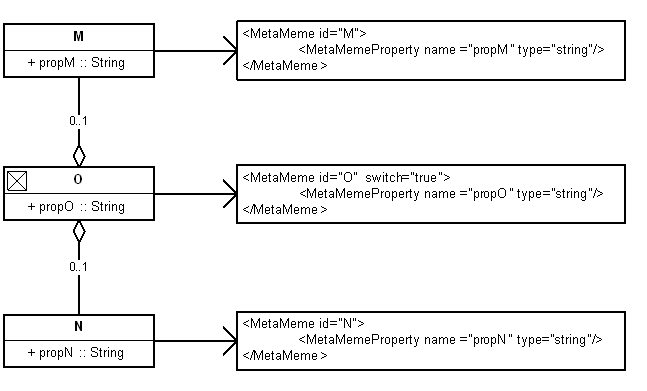

An advanced form of member metameme usage is Exclusive Membership. An exclusive membership relationship means that only one of the children defined by the metameme may be present in a child meme. A metameme with such an exclusive membership arrangement is known as a Switch Metameme. In diagrams, a metameme is declared to be a switch by adding a box with an X inside it to the left of the metameme ID. In the XML exchange document, it is declared with the optional Boolean attribute switch in the MetaMeme element. The switch declaration only affects member metamemes. It has no effect on property definitions or extension/enhancement relationships.

Metameme O declares M and N as member metamemes. Because O is a switch metameme, any child meme of it can have either M or N.

The figure below shows the XML exchange format form of M, N and O

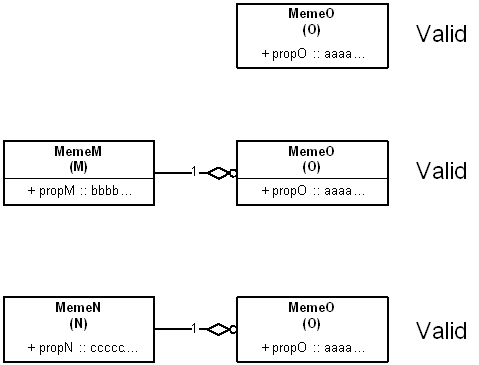

The figure below is a graph with three possible valid membership combinations for M,N and O child memes MemeM, MemeN and MemeO.

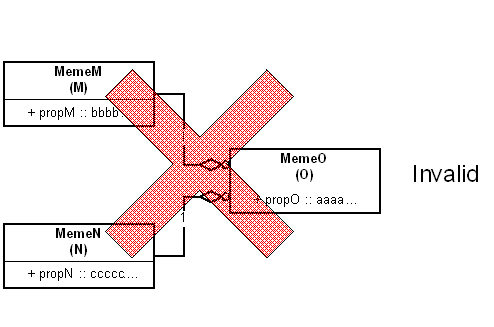

The figure below shows an invalid membership combination of MemeM, MemeN and MemeO. If you want to combine switched members with non-switched members, use enhancement.

Distinct Membership and the distinct Attribute

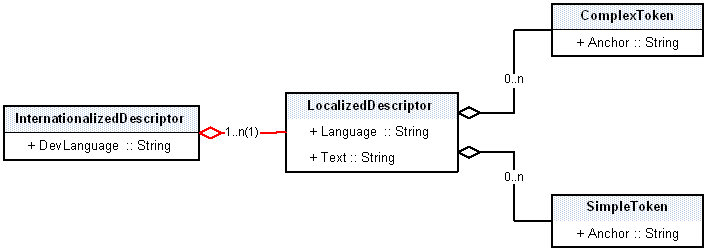

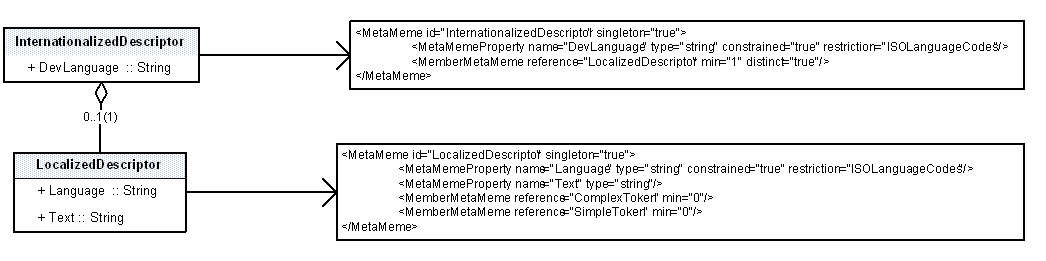

One advanced property of membership is the optional distinct attribute on metamemes. Distinct is used when the cardinality of a member metameme is greater than one, but the child meme requires that each individual member meme be distinct. To explain in detail, we shall examine the InternationalizedDescriptor metameme from Memetic’s standard metamemes package and is part of the descriptor family, which is used to provide stimuli to clients and AI agents. Descriptors are the technical workhorses of stimuli and the InternationalizedDescriptor is a schema for dynamic, multilingual text. If you need dynamic text, or text in multiple languages, or dynamic text in multiple languages, InternationalizedDescriptor is your tool.

InternationalizedDescriptor is shown in the figure below. It has one or more LocalizedDescriptor members. Each one of these is used to represent a different language. The designer is free to add as many languages as she wants, but each language may occur only once. Obviously, she wants each child meme of LocalizedDescriptor to be unique as it makes no sense for the occurrence of the English LocalizedDescriptor to be two; yet she needs to be able to add an unlimited number of different LocalizedDescriptor memes. Because LocalizedDescriptor’s membership in InternationalizedDescriptor is set to be distinct, each member meme (one per language) of an InternationalizedDescriptor child meme is distinct, but an unlimited number of memes of type LocalizedDescriptor may be added .

On a graph, distinct membership is shown by adding an optional Boolean “distinct” in parenthesis to the right of the cardinality. The membership link between InternationalizedDescriptor and LocalizedDescriptor is shown in red to highlight this. The membership cardinality of LocalizedDescriptor is 1..n (1). This means that it must occur at least once, may occur any number of times and the 1 in parenthesis is indicative of a boolean TRUE. If no distinct flag appears on the link (as is the case with LocalizedDescriptor’s members); then the member metameme is not forced to be distinct.

The figure below shows the XML exchange format elements of both the InternationalizedDescriptor and LocalizedDescriptor, including the distinct status of LocalizedDescriptor as a member of InternationalizedDescriptor.

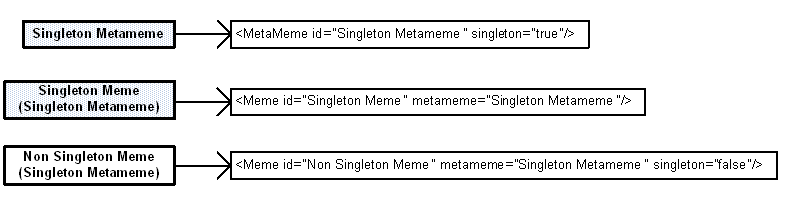

Unique Entities (a.k.a Singletons)

There are times when the designer may want exactly one instance of a given meme to be created; no more, no less. This is determined by an optional Boolean attribute that may be set at either the metameme or meme level called Singleton. If a meme is a singleton, then it will have a unique Entity. When it is loaded by the interpreter, an entity will be created and no further entities may be created. In Graphyne, all future references to the meme are redirected to the entity. Memes inherit the singleton status of their parent metameme, though they may override it. Metamemes flagged as singletons are not actually unique entities themselves and have no restrictions on the number of child memes. They merely indicate that all child memes are unique.

In Memetic graphs, the singleton status of a meme or metameme is indicated by shading the title region. In the figure below, Singleton Metameme is a singleton as indicated by the “singleton” attribute in the MetaMeme XML entity below. Its children would automatically inherit this attribute as Singleton Meme does. Non Singleton Meme explicitly declares itself as a non singleton by setting the “singleton” attribute to false in its Meme XML entity. Singleton Metameme and Singleton Meme have shaded title regions, while Non Singleton Meme does not.

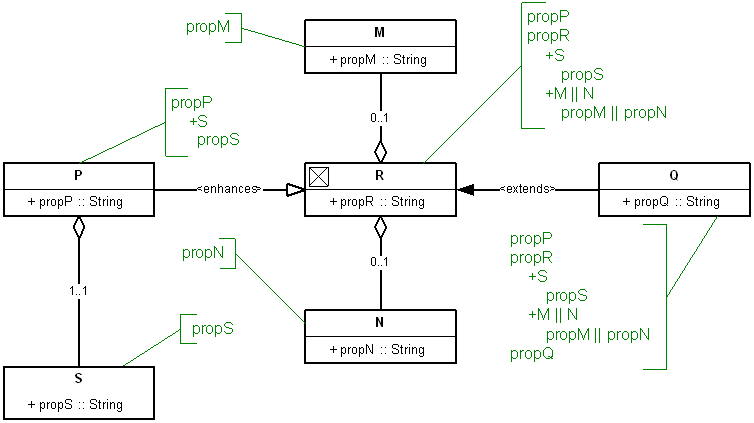

A Taste of Complexity

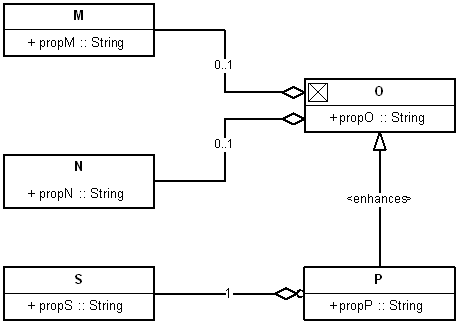

It is possible to use metamemes to design extremely complex and interconnected data structures. The example in the figure below makes use of member metamemes, extensions, enhancements and switches. The green labels indicate what properties and members that entities created from any given child meme could have.

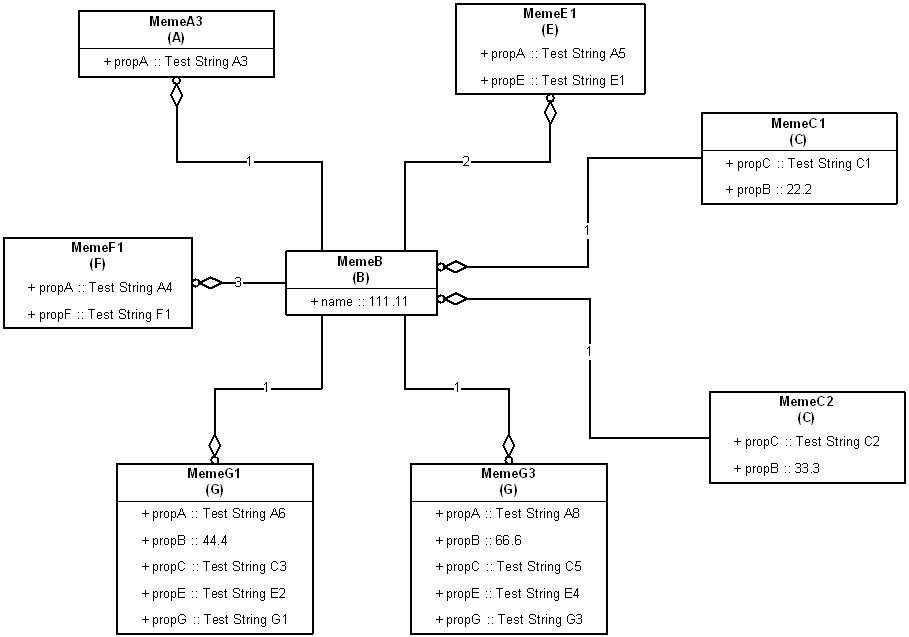

The Graphyne has a number of Memetic modules used for testing purposes. Chief among these is Examples, which is available Graphyne’s Git repository. The uppermost figure below shows a metameme snippet from Examples and the lower figure below shows some of the child memes from the same module. Metamemes G, F and E extend A, which has B as a member. In the memes snippet, you can see that several memes of differing types have MemeB as a member. It is possible for any number of memes to have the same distinct meme as a member. This enhances reusability at the meme level. Another quirk is that C (and ultimately G as well) extends B, while D enhances it. This allows a de-facto recursive membership at the entity level. Also note that while G ultimately extends both A and B, this does not mean that child memes of G can have G memes as members. They may only have memes of type C and B.

Traverse Path Syntax

Traverse Paths are Memetic’s selection methodology. They allow you to select entities, based on the topology of the graph. You can either select them directly, based on their meme, or you can traverse the graph from one entity to another. Traverse paths essentially act as roadmaps. Some examples of traverse paths include:

- ExampleModule.ExampleMeme1::ExampleModule.ExampleMeme2

- ExampleMeme1::ExampleMeme2

- ExampleMeme1>>ExampleMeme2

- ExampleMeme1<<ExampleMeme2

- <<ExampleMeme1

- (entityProp = 1)ExampleMeme1

- ExampleMeme1::(entityProp = 1)[linkProp <>]ExampleMeme2

The overall structure of a traverse path is as follows: <SelectEntityOneHopAway><SelectEntityOneHopFurther><Etc><Etc>

In the examples above, we either selected the entity one hop away (always ExampleMeme1) and sometimes an entity two hops away (ExampleMeme2). Note that we always make the selection of the entity based on its parent meme.

The detailed selection of an individual entity can be a bit more complex: <Directionality> <EntityVariables><LinkVariables><EntityOneHopAway>

Directionality

All links have a direction. When two entities are linked together, the link is created from one entity to another. In therm of link directionality, these are outbound and inbound links, respectively. The link directionality goes at the leading edge of a hop selector. It can be >> (outbound), << (inbound) or :: (bidirectional). If the selector is bidirectional, then it will follow both inbound and outbound links.

Path | Notes — | — ExampleMeme1::ExampleMeme2 | Hops from 1 to 2, regardless of direction ExampleMeme1>>ExampleMeme2 | Hops outbound links from 1 to 2 ExampleMeme1<<ExampleMeme2 | Hops inbound links from 1 to 2

EntityAttributes

If you want to limit the selected entities based on attribute values, you can add that as part of the hop selector criteria. They go into parenthesis, e.g. (a = 1), (b != 1), etc.

Operator | Meaning :—: | :—: = | Equal To != | Not Equal To > | Greater Than < | Less Than => | Equal To or Greater Than =< | Equal To or Less Than <> | In >< | Not In

The last two entries do not require a value. They simple test whether or not the attribute exists in the entity. Entity attributes can be chained together in a node selector, e.g. (a = 1)(b != 2)(c <>)

Link Attributes: Just like entities, links can have attributes. Their selection works just as with entity attributes. They are enclosed by brackets. E.g. [a = 1].

Memetic does not currently have a syntax for assigning attributes via command and relies on the api of the graph engine. for this.

Entity:

The entities in a node selector are based on parent memes and behave the same as classpaths in many object oriented programming languages, such as Java and Python. The meme ID is based on its path structure within the filesystem of the repository (the folder where the schema is stored). Templates (memes, metamemes and restrictions) are stored in XML files. An XML file containing templates is known as a “module” in Memetic. A group of related modules in the same folder is known as a “package”. Packages may contain child packages. Memetic templates can be distributed as individual modules or as packages. A Memetic repository is a file system location where packages and modules are stored. This is a critical part of the philosophy behind Memetic, allowing designers to re-use and trade work.

Repository

- -File1 (Module1)

- - -Meme1

- -Folder (Package)

- - -File2 (Module2)

- - - -Meme2

- - -File3 (Module3)

- - - -Meme3

Traverse paths are either full or relative. A full traverse path is a combination of the filepath of the module relative to the repository where templates are stored, with the template name concatenated at the end. A period is used as a separator. A relative traverse path is an abbreviated version for use within a package or module. A relative traverse path within a module is simply the id (name) of the template. Within a package, it is possible to write the path relative to the package.

The diagram above shows an example repository. In it are a single file called Module1 and a single folder called Package. Package in turns has two files, Module2 and Module3. Each module in our example contains exactly one template; a meme. The full traverse paths of the three memes would be:

- File1.Meme1

- Folder.File2.Meme2

- Folder.File3.Meme3

If Meme2 were to reference Meme3, either a full or relative traverse path can be used. The relative traverse path would be File3.Meme3. Properties are also present in the traverse path, so a property abc in Meme3 would be at Folder.File3.Meme3.abc.

Further Notes on Traverse Paths

Concatenated Traverse Paths

It is possible to reference members of members directly, using concatenated traverse paths. For example, a designer of a fantasy role playing game might have a meme for an orc. This Orc meme might be in an XML schema file (module) named Mobs. Orc has a member meme for endocontainer inventory called Inventory from the Inventory module. This inventory in turn has a member called GoldCoin, from the Loot module. Just as a reminder, the full traverse paths of Orc and Inventory are:

- FantasyRPG.Mobs.Orc (found in /FantasyRPG/Mobs.xml)

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory (found in /FantasyRPG/Inventory.xml)

- FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin (found in /FantasyRPG/Loot.xml)

To access the a gold coin entity held int he inventory of the Orc entity, the designer has to navigate two traverse paths in tandem. The first is the reference from Orc to Inventory, reachable using either the relative traverse path Inventory.Inventory or the full traverse path FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory. The second is the reference from the inventory to the coin usinf either the relative traverse path Loot.GoldCoin or the full traverse path FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin. When multiple hops are required to access a member, a double colon ("::") separator is used to concatenate the constituent traverse paths. The following four concatenated traverse paths are valid for the orc-coin reference:

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::Loot.GoldCoin

- Inventory.Inventory::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin

- Inventory.Inventory::Loot.GoldCoin

Wildcards

It is possible to use asterisks as wild cards in place of one or more members in concatenated paths. This becomes necessary as members can contain other members and the result can be akin to a matryoshka doll. If a designer were looking for a gold coin on an orc and did not know if it was directly in the endocontainer inventory of the orc, or in a bag held by the orc (as a member of the bag, which is a member of the orc’s endoncontainer inventory), or she wanted all of the coins on the orc, regardless of location, she could insert wildcard into the concatenated path.

- *::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin

- *::Loot.GoldCoin

Note that the latter option is relative to the orc meme, so the relative traverse path must be written appropriately. The wildcard can be at any level except the final destination (Loot.GoldCoin in this case). If the designer were looking for gold coins held inside containers (at any level), but not directly in the endocontainer inventory of the orc itself, the following paths would be correct:

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::*::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::*::Loot.GoldCoin

- Inventory.Inventory::*::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin

- Inventory.Inventory::*::Loot.GoldCoin

Properties of Members

It is possible to reference members of members directly, using concatenated traverse paths. To access the Weight property of a cold coin in the inventory of an orc (and for the sake of simplicity in this example, only directly in the inventory of the orc), the following paths are valid:

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin.Wieght

- FantasyRPG.Inventory.Inventory::Loot.GoldCoin.Wieght

- Inventory.Inventory::FantasyRPG.Loot.GoldCoin.Wieght

- Inventory.Inventory::Loot.GoldCoin.Wieght

Wild cards can also be used in place of parent members of properties, leaving only the property name. This can be very useful in certain situations. If the designer wanted to check the weight of the orc's endocontainer inventory, he could easily get all of the Weight properties of members of Inventory.Inventory: Inventory.Inventory::*.Weight

If the designer wanted to check the Weight of the orc (not just endocontainer inventory), he could easily get all of the weight properties of orc (if orc has such a property) and all members: *.Wieght

Mass Content Creation with Implicit Memes

Memetic includes an optional provision for mass content creation via tables; if the graph engine supports it. There may be situations where there may be a very large number of memes created against a single metameme. In such situations, the meme designer may find it more comfortable to work in a spreadsheet, with individual memes being on the rows axis and properties being defined on the column axis. While it is certainly possible to write exporters to write this, most relational databases have some utility available (built in or third party commercial or open source) for importing spreadsheet content into that database.

For example, suppose someone was creating a restaurant review app. She would want users to be able to add new restaurants as they opened and these restaurants would all be entities. She would want to create templates for users to use when creating new restaurants, so that they don’t need to fill everything out themselves. She would only need a single restaurant metameme to define the basic concept of a restaurant, but there are many. many different types of restaurants. We have take-out, sit-in, cafes, catering halls, taverns, fast-food, food trucks, etc. etc. Then we have the different cuisine types, the different price ranges, different levels of formality, etc, etc. She might want to define these in a large spreadsheet table and then create memes from them, so that when a user wants to add that new Tex-Mex food truck, he can select that phenotype from the menu and then concentrate on the real differentiators.

To accomplish this, Memetic uses something called Implicit Memes.

Implicit Memes

If you wish to create implicit memes, you set this up in your metameme definition. Here, you will declare which table in the database the memes are being created from and which columns map to which properties in the meme. The rule is one table maps to exactly one metameme and one row within that table corresponds to one meme.

Let us consider a very simple implicit metameme definition:

We see an attribute on the MetaMeme element, called dynamic. If this is “implicit”, then this metameme is considered implicit and all of its memes will be built from a table.

The MetaMemeProperty elements are unchanged.

There is a new element, called ImplicitMemeMasterData:

It has an attribute called table. This declares which table (presumably a relational database table) holds the meme definitions.

It has an attribute called primaryKeyColumn. This is the table column that holds the meme ID. It should be unique for each row: i.e. a primary key in the table.

Each MetaMemeProperty element gets a corresponding PropertySource element within the ImplicitMemeMasterData element. It has two attributes property and column, indicating which properties map to which columns.

We have a stub meme element for this metameme:

The implicitMeme attribute (set to true) signals to the graph engine that it should look in the table for the meme definitions. That’s it. The designer now defines lots of different IsChild memes in a spreadsheet and uses whatever technical workflow used by the graph engine to make them ready to use.

Implicit Meme Relationships (forward and backward references)

It is possible to define relationships between implicit memes and between normal memes and implicit memes. There are two ways of doing this, depending on what the designer needs; forward and back references. Forward references are used when there are fixed children of the creating meme’s entities at runtime. E.g if every A gets a B child element and A knows ahead of time what B is. If n is greater than one, then back references are used. If A can get several B’s, then back references allow the Bs to refer back to A as their parent. Back references can also be used for 1:1 relationships, but they are slightly more complex to set up (requiring a parent column to be maintained). Forward references are a usability feature.

Forward References

Forward references are the simplest relationship. The parent points to the child. Consider the following metameme definition:

This metameme definition introduces a Relationship element. Within this element, there is a ForwardReference element. It has two attributes: childColumn declares which column (in the HasChild table) points to the corresponding IsChild meme. traversePath declares the path needed to get from HasChild to IsChild. Implicit meme element clusters can have more than one hop, so it is possible for IsChild to have IsGandChild in turn. If this is so, then HasChild also needs to know about IsGrandChild and be able to navigate to it via IsChild.

Back References

Let’s add a new child metameme and make it a back reference. Its structure is similar to the IsChild metameme definition:

Now let us extend HasChild, to include affordance for back references from IsBRChild.

We see a new element within Relationships, BackReference. Back reference adds parentColumn and backReferenceColumn attributes. The first is just a reference to HasChild’s primary key column. The second is a column within the IsBRChild table, where were also put this primary key. When the graph engine loads the schema, it will map out the back references to parent memes and then build them out as if they were defined directly in XML>