tomodachi ⌁ a lightweight µservice lib ⌁ for Python 3

tomodachi [友達] means friends — 🦊🐶🐻🐯🐮🐸🐍 — a suitable name for microservices working together. ✨✨

events messaging api pubsub sns+sqs amqp http queues handlers scheduling tasks microservice tomodachi

tomodachi is a library designed to make it easy for devs to build

microservices using asyncio on Python.

Includes ready implementations to support handlers built for HTTP requests, websockets, AWS SNS+SQS and RabbitMQ / AMQP for 🚀 event based messaging, 🔗 intra-service communication and 🐶 watchdog handlers.

- HTTP request handlers (API endpoints) are sent requests via the

aiohttpserver library. 🪢 - Events and message handlers are hooked into a message bus, such as a queue, from for example AWS (Amazon Web Services) SNS+SQS (

aiobotocore), RabbitMQ / AMQP (aioamqp), etc. 📡

Using the provided handler managers, the need for devs to interface with low-level libs directly should be lower, making it more of a breeze to focus on building the business logic. 🪄

tomodachi has a featureset to meet most basic needs, for example...

-

🦸⋯ Graceful termination of consumers, listeners and tasks to ensure smooth deployments. -

⏰⋯ Scheduled function execution (cron notation / time interval) for building watchdog handlers. -

🍔⋯ Execution middleware interface for incoming HTTP requests and received messages. -

💌⋯ Simple envelope building and parsing for both receiving and publishing messages. -

📚⋯ Logging support viastructlogwith template loggers for both "dev console" and JSON output. -

⛑️⋯ Loggers and handler managers built to support exception tracing, from for example Sentry. -

📡⋯ SQS queues with filter policies for SNS topic subscriptions filtering messages on message attributes. -

📦⋯ Supports SQS dead-letter queues via redrive policy -- infra orchestration from service optional. -

🌱⋯ Designed to be extendable -- most kinds of transport layers or event sources can be added.

Quicklinks to the documentation 📖

This documentation README includes information on how to get started with services, what built-in functionality exists in this library, lists of available configuration parameters and a few examples of service code.

Visit https://tomodachi.dev/ for additional documentation. 📔

Handler types / endpoint built-ins. 🛍️

- HTTP and WebSocket endpoints

- AWS SNS+SQS event messaging

- RabbitMQ / AMQP messaging

- Scheduled functions and cron

Service options to tweak handler managers. 🛠️

Use the features you need. 🌮

- Middleware functionality

- Function signature keywords

- Logging and log formatters

- OpenTelemetry instrumentation

Recommendations and examples. 🧘

Please note -- this library is a work in progress. 🐣

Consider tomodachi as beta software. This library follows an unregular

release schedule. There may be breaking changes between 0.x versions.

Usage

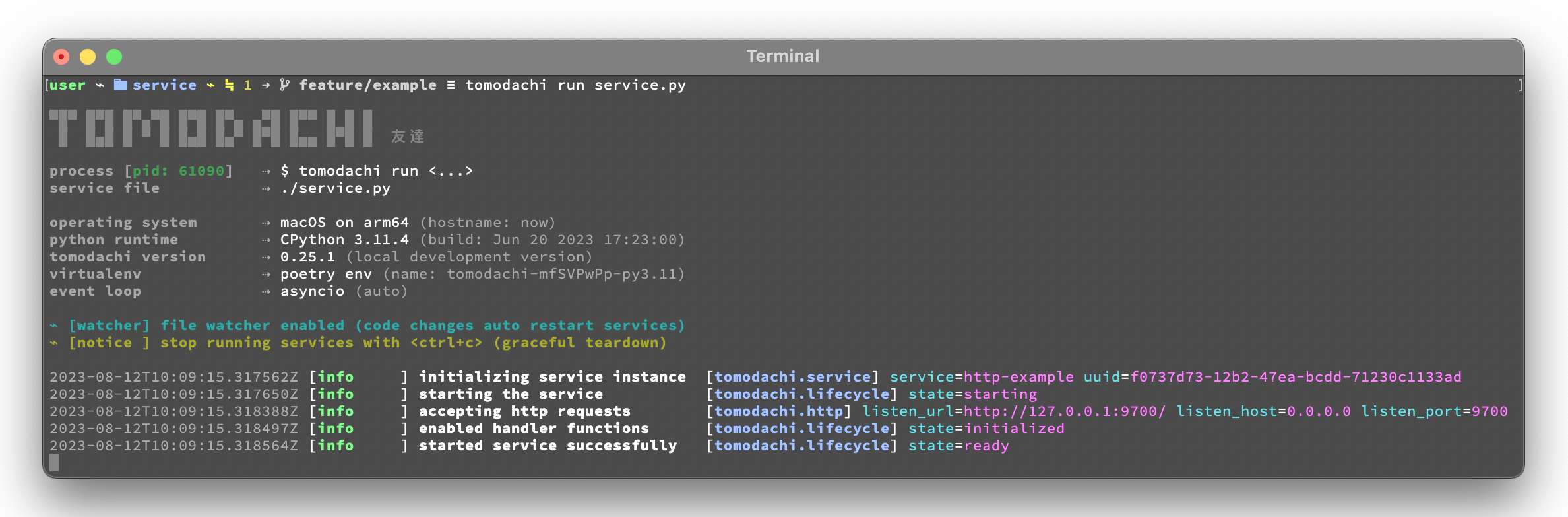

tomodachi is used to execute service code via command line interface

or within container images. It will be installed automatically when the

package is installed in the environment.

The CLI endpoint tomodachi is then used to run services defined as

tomodachi service classes.

Start a service with its class definition defined in ./service/app.py

by running tomodachi run service/app.py. Finally stop the service with

the keyboard interrupt <ctrl+c>.

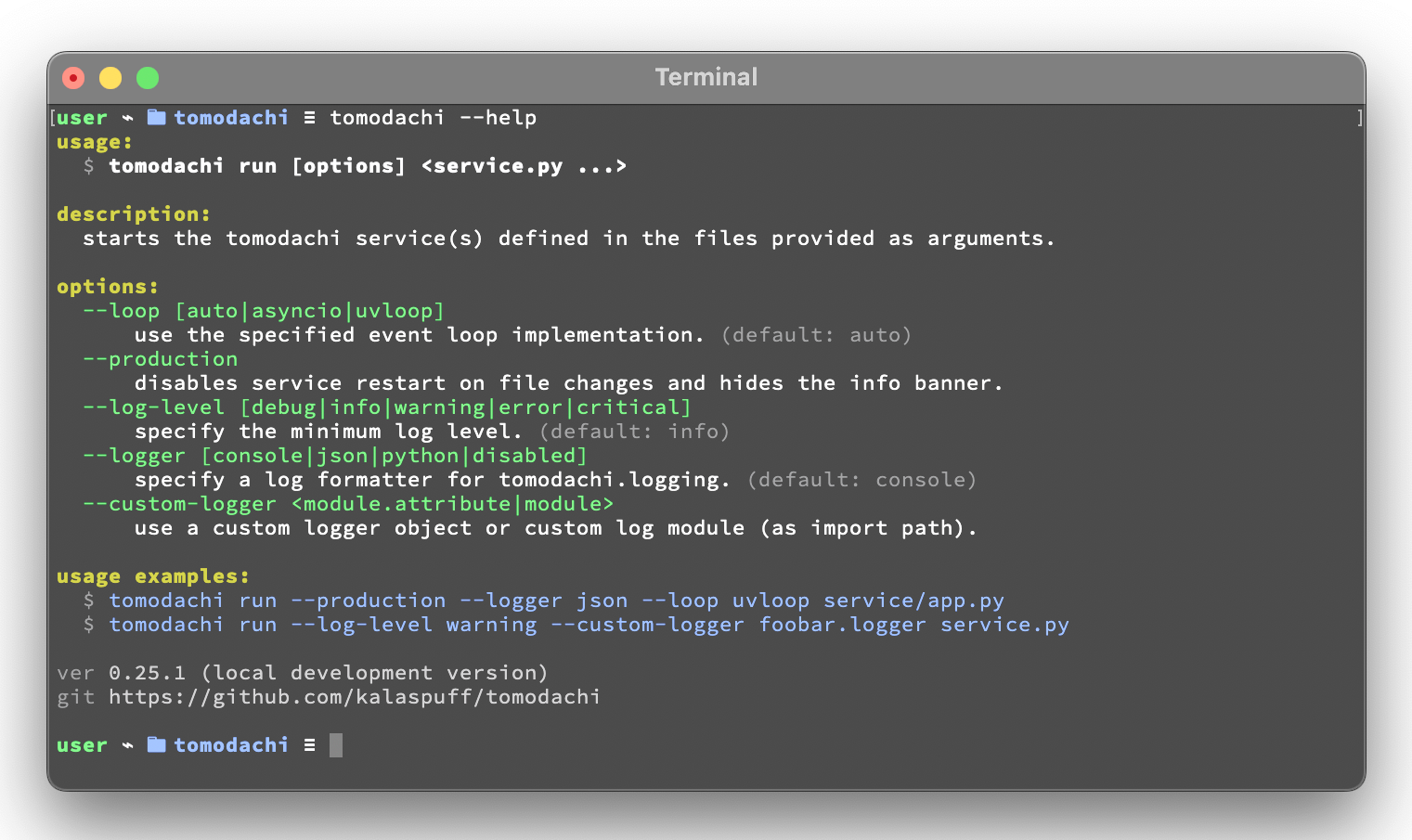

The run command has some options available that can be specified with arguments to the CLI.

Most options can also be set as an environment variable value.

For example setting environment TOMODACHI_LOGGER=json will yield the

same change to the logger as if running the service using the argument

--logger json.

| 🧩 | --loop [auto|asyncio|uvloop] |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_LOOP=... |

The value for --loop can either be set to asyncio, uvloop or

auto. The uvloop value can only be used if uvloop is installed in

the execution environment. Note that the default auto value will

currently end up using the event loop implementation that is preferred

by the Python interpreter, which in most cases will be asyncio.

| 🧩 | --production |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_PRODUCTION=1 |

Use --production to disable the file watcher that restarts the service

on file changes and to hide the startup info banner.

⇢ recommendation ✨👀

⇢ Highly recommended to enable this option for built docker images and

for builds of services that are to be released to any environment. The

only time you should run without the --production option is during

development and in local development environment.

| 🧩 | --log-level [debug|info|warning|error|critical] |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_LOG_LEVEL=... |

Set the minimum log level for which the loggers will emit logs to their

handlers with the --log-level option. By default the minimum log level

is set to info (which includes info, warning, error and

critical, resulting in only the debug log records to be filtered

out).

| 🧩 | --logger [console|json|python|disabled] |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_LOGGER=... |

Apply the --logger option to change the log formatter that is used by

the library. The default value console is mostly suited for local

development environments as it provides a structured and colorized view

of log records. The console colors can be disabled by setting the env

value NO_COLOR=1.

⇢ recommendation ✨👀

⇢ For released services / images it's recommended to use the json

option so that you can set up structured log collection via for

example Logstash, Fluentd, Fluent Bit, Vector, etc.

If you prefer to disable log output from the library you can use

disabled (and presumably add a log handler with another

implementation).

The python option isn't recommended, but available if required to use

the loggers from Python's built-in logging module. Note that the

built-in logging module will be used any way. as the library's

loggers are both added as handlers to logging.root and has propagation

of records through to logging as well.

| 🧩 | --custom-logger <module.attribute|module> |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_CUSTOM_LOGGER=... |

If the template loggers from the option above doesnt' cut it or if you

already have your own logger (preferably a structlog logger) and

processor chain set up, you can specify a --custom-logger which will

also make tomodachi use your logger set up. This is suitable also if

your app is using a custom logging setup that would differ in output

from what the tomodachi loggers outputs.

If your logger is initialized in for example the module

yourapp.logging and the initialized (structlog) logger is aptly

named logger, then use --custom-logger yourapp.logging.logger (or

set as an env value TOMODACHI_CUSTOM_LOGGER=yourapp.logging.logger).

The path to the logger attribute in the module you're specifying must

implement debug, info, warning, error, exception, critical

and preferably also new(context: Dict[str, Any]) -> Logger (as that is

what primarily will be called to create (or get) a logger).

Although non-native structlog loggers can be used as custom loggers,

it's highly recommended to specify a path that has been assigned a

value from structlog.wrap_logger or structlog.get_logger.

| 🧩 | --opentelemetry-instrument |

|---|---|

| 🖥️ | TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT=1 |

Use --opentelemetry-instrument to enable OpenTelemetry auto

instrumentation of the service and libraries for which the environment

has installed instrumentors.

If tomodachi is installed in the environment, using the argument

--opentelemetry-instrument (or setting the

TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT=1 env variable value) is mostly

equivalent to starting the service using the opentelemetry-instrument

CLI -- OTEL distros, configurators and instrumentors will be loaded

automatically and OTEL_* environment values will be processed in the

same way.

Getting started 🏃

First off -- installation using poetry is fully supported and battle-tested (pip works just as fine)

Install tomodachi in your preferred way, wether it be poetry, pip,

pipenv, etc. Installing the distribution will give your environment

access to the tomodachi package for imports as well as a shortcut to

the CLI alias, which later is used to run the microservices you build.

local ~$ pip install tomodachi

> ...

> Installing collected packages: ..., ..., ..., tomodachi

> Successfully installed ... ... ... tomodachi-x.x.xx

local ~$ tomodachi --version

> tomodachi x.xx.xxtomodachi can be installed together with a set of "extras" that will

install a set of dependencies that are useful for different purposes.

The extras are:

-

uvloop: for the possibility to start services with the--loop uvloopoption. -

protobuf: for protobuf support in envelope transformation and message serialization. -

aiodns: to useaiodnsas the DNS resolver foraiohttp. -

brotli: to usebrotlicompression inaiohttp. -

opentelemetry: for OpenTelemetry instrumentation support. -

opentelemetry-exporter-prometheus: to use the experimental OTEL meter provider for Prometheus.

Services and their dependencies, together with runtime utilities like

tomodachi, should preferably always be installed and run in isolated

environments like Docker containers or virtual environments.

Building blocks for a service class and microservice entrypoint

-

import tomodachiand create a class that inheritstomodachi.Service, it can be called anything... or justServiceto keep it simple. - Add a

nameattribute to the class and give it a string value. Having anameattribute isn't required, but good practice. - Define an awaitable function in the service class -- in this example we'll use it as an entrypoint to trigger code in the service by decorating it with one of the available invoker decorators. Note that a service class must have at least one decorated function available to even be recognized as a service by

tomodachi run. - Decide on how to trigger the function -- for example using HTTP, pub/sub or on a timed interval, then decorate your function with one of these trigger / subscription decorators, which also invokes what capabilities the service initially has.

Further down you'll find a desciption of how each of the built-in invoker decorators work and which keywords and parameters you can use to change their behaviour.

Note: Publishing and subscribing to events and messages may require user credentials or hosting configuration to be able to access queues and topics.

For simplicity, let's do HTTP:

- On each POST request to

/sheep, the service will wait for up to one whole second (pretend that it's performing I/O -- waiting for response on a slow sheep counting database modification, for example) and then issue a 200 OK with some data. - It's also possible to query the amount of times the POST tasks has run by doing a

GETrequest to the same url,/sheep. - By using

@tomodachi.httpan HTTP server backed byaiohttpwill be started on service start.tomodachiwill act as a middleware to route requests to the correct handlers, upgrade websocket connections and then also gracefully await connections with still executing tasks, when the service is asked to stop -- up until a configurable amount of time has passed.

import asyncio

import random

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "sleepy-sheep-counter"

_sheep_count = 0

@tomodachi.http("POST", r"/sheep")

async def add_to_sheep_count(self, request):

await asyncio.sleep(random.random())

self._sheep_count += 1

return 200, str(self._sheep_count)

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/sheep")

async def return_sheep_count(self, request):

return 200, str(self._sheep_count)Run services with:

local ~/code/service$ tomodachi run service.pyBeside the currently existing built-in ways of interfacing with a service, it's possible to build additional function decorators to suit the use-cases one may have.

To give a few possible examples / ideas of functionality that could be coded to call functions with data in similar ways:

- Using Redis as a task queue with configurable keys to push or pop onto.

- Subscribing to Kinesis or Kafka event streams and act on the data received.

- An abstraction around otherwise complex functionality or to unify API design.

- As an example to above sentence; GraphQL resolver functionality with built-in tracability and authentication management, with a unified API to application devs.

Additional examples will follow with different ways to trigger functions in the service

Of course the different ways can be used within the same class, for example the very common use-case of having a service listening on HTTP while also performing some kind of async pub/sub tasks.

Basic HTTP based service 🌟

Code for a simple service which would service data over HTTP, pretty similar, but with a few more concepts added.

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "http-example"

# Request paths are specified as regex for full flexibility

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/resource/(?P<id>[^/]+?)/?")

async def resource(self, request, id):

# Returning a string value normally means 200 OK

return f"id = {id}"

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/health")

async def health_check(self, request):

# Return can also be a tuple, dict or even an aiohttp.web.Response

# object for more complex responses - for example if you need to

# send byte data, set your own status code or define own headers

return {

"body": "Healthy",

"status": 200,

}

# Specify custom 404 catch-all response

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code=404)

async def error_404(self, request):

return "error 404"RabbitMQ or AWS SNS+SQS event based messaging service 🐰

Example of a service that calls a function when messages are published on an AMQP topic exchange.

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "amqp-example"

# The "message_envelope" attribute can be set on the service class to build / parse data.

# message_envelope = ...

# A route / topic on which the service will subscribe to via RabbitMQ / AMQP

@tomodachi.amqp("example.topic")

async def example_func(self, message):

# Received message, fordarding the same message as response on another route / topic

await tomodachi.amqp_publish(self, message, routing_key="example.response")

AMQP – Publish to exchange / routing key – tomodachi.amqp_publish

await tomodachi.amqp_publish(service, message, routing_key=routine_key, exchange_name=...)-

serviceis the instance of the service class (from within a handler, useself) -

messageis the message to publish before any potential envelope transformation -

routing_keyis the routing key to use when publishing the message -

exchange_nameis the exchange name for publishing the message (default: "amq.topic")

For more advanced workflows, it's also possible to specify overrides for the routing key prefix or message enveloping class.

AWS SNS+SQS event based messaging service 📡

Example of a service using AWS SNS+SQS managed pub/sub messaging. AWS

SNS and AWS SQS together brings managed message queues for

microservices, distributed systems, and serverless applications hosted

on AWS. tomodachi services can customize their enveloping

functionality to both unwrap incoming messages and/or to produce

enveloped messages for published events / messages. Pub/sub patterns are

great for scalability in distributed architectures, when for example

hosted in Docker on Kubernetes.

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "aws-example"

# The "message_envelope" attribute can be set on the service class to build / parse data.

# message_envelope = ...

# Using the @tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs decorator to make the service create an AWS SNS topic,

# an AWS SQS queue and to make a subscription from the topic to the queue as well as start

# receive messages from the queue using SQS.ReceiveMessages.

@tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs("example-topic", queue_name="example-queue")

async def example_func(self, message):

# Received message, forwarding the same message as response on another topic

await tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs_publish(self, message, topic="another-example-topic")

AWS – Publish message to SNS – tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs_publish

await tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs_publish(service, message, topic=topic)-

serviceis the instance of the service class (from within a handler, useself) -

messageis the message to publish before any potential envelope transformation -

topicis the non-prefixed name of the SNS topic used to publish the message

Additional function arguments can be supplied to also include message_attributes, and / or group_id + deduplication_id.

For more advanced workflows, it's also possible to specify overrides for the SNS topic name prefix or message enveloping class.

AWS – Send message to SQS – tomodachi.sqs_send_message

await tomodachi.sqs_send_message(service, message, queue_name=queue_name)-

serviceis the instance of the service class (from within a handler, useself) -

messageis the message to publish before any potential envelope transformation -

queue_nameis the SQS queue url, queue ARN or non-prefixed queue name to be used

Additional function arguments can be supplied to also include message_attributes, and / or group_id + deduplication_id.

For more advanced workflows, it's also possible to set delay seconds, define a custom message body formatter, or to specify overrides for the SNS topic name prefix or message enveloping class.

Scheduling, inter-communication between services, etc. ⚡️

There are other examples available with code of how to use services with self-invoking methods called on a specified interval or at specific times / days, as well as additional examples for inter-communication pub/sub between different services on both AMQP or AWS SNS+SQS as shown above. See more at the examples folder.

Run the service 😎

# cli alias is set up automatically on installation

local ~/code/service$ tomodachi run service.py

# alternatively using the tomodachi.run module

local ~/code/service$ python -m tomodachi.run service.pyDefaults to output startup banner on stdout and log output on stderr.

HTTP service acts like a normal web server.

local ~$ curl -v "http://127.0.0.1:9700/resource/1234"

# > HTTP/1.1 200 OK

# > Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

# > Server: tomodachi

# > Content-Length: 9

# > Date: Sun, 16 Oct 2022 13:38:02 GMT

# >

# > id = 1234Getting an instance of a service

If the a Service instance is needed outside the Service class itself, it

can be acquired with tomodachi.get_service. If multiple Service

instances exist within the same event loop, the name of the Service can

be used to get the correct one.

import tomodachi

# Get the instance of the active Service.

service = tomodachi.get_service()

# Get the instance of the Service by service name.

service = tomodachi.get_service(service_name)Stopping the service

Stopping a service can be achieved by either sending a SIGINT

<ctrl+c> or SIGTERM signal to to the tomodachi Python process, or

by invoking the tomodachi.exit() function, which will initiate the

termination processing flow. The tomodachi.exit() call can

additionally take an optional exit code as an argument, which otherwise

will default to use exit code 0.

-

SIGINTsignal (equivalent to using <ctrl+c>) -

SIGTERMsignal -

tomodachi.exit()ortomodachi.exit(exit_code)

The process' exit code can also be altered by changing the value of

tomodachi.SERVICE_EXIT_CODE, however using tomodachi.exit with an

integer argument will override any previous value set to

tomodachi.SERVICE_EXIT_CODE.

All above mentioned ways of initiating the termination flow of the service will perform a graceful shutdown of the service which will try to await open HTTP handlers and await currently running tasks using tomodachi's scheduling functionality as well as await tasks processing messages from queues such as AWS SQS or RabbitMQ.

Some tasks may timeout during termination according to used

configuration (see options such as

http.termination_grace_period_seconds) if they are long running tasks.

Additionally container handlers may impose additional timeouts for how

long termination are allowed to take. If no ongoing tasks are to be

awaited and the service lifecycle can be cleanly terminated the shutdown

usually happens within milliseconds.

Function hooks for service lifecycle changes

To be able to initialize connections to external resources or to perform graceful shutdown of connections made by a service, there's a few functions a service can specify to hook into lifecycle changes of a service.

| Magic function name | When is the function called? | What is suitable to put here |

|---|---|---|

_start_service |

Called before invokers / servers have started. | Initialize connections to databases, etc. |

_started_service |

Called after invokers / server have started. | Start reporting or start tasks to run once. |

_stopping_service |

Called on termination signal. | Cancel eventual internal long-running tasks. |

_stop_service |

Called after tasks have gracefully finished. | Close connections to databases, etc. |

Changes to a service settings / configuration (by for example modifying

the options values) should be done in the __init__ function instead

of in any of the lifecycle function hooks.

Good practice -- in general, make use of the _start_service (for

setting up connections) in addition to the _stop_service (to close

connections) lifecycle hooks. The other hooks may be used for more

uncommon use-cases.

Lifecycle functions are defined as class functions and will be called by the tomodachi process on lifecycle changes:

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "example"

async def _start_service(self):

# The _start_service function is called during initialization,

# before consumers or an eventual HTTP server has started.

# It's suitable to setup or connect to external resources here.

return

async def _started_service(self):

# The _started_service function is called after invoker

# functions have been set up and the service is up and running.

# The service is ready to process messages and requests.

return

async def _stopping_service(self):

# The _stopping_service function is called the moment the

# service is instructed to terminate - usually this happens

# when a termination signal is received by the service.

# This hook can be used to cancel ongoing tasks or similar.

# Note that some tasks may be processing during this time.

return

async def _stop_service(self):

# Finally the _stop_service function is called after HTTP server,

# scheduled functions and consumers have gracefully stopped.

# Previously ongoing tasks have been awaited for completion.

# This is the place to close connections to external services and

# clean up eventual tasks you may have started previously.

returnExceptions raised in _start_service or _started_service will

gracefully terminate the service.

Graceful termination of a service (SIGINT / SIGTERM)

When the service process receives a SIGINT or SIGTERM signal (or tomodachi.exit() is called) the service begins the process for graceful termination, which in practice means:

- The service'

_stopping_servicemethod, if implemented, is called immediately upon the received signal. - The service stops accepting new HTTP connections and closes keep-alive HTTP connections at the earliest.

- Already established HTTP connections for which a handler call is awaited called are allowed to finish their work before the service stops (up to

options.http.termination_grace_period_secondsseconds, after which the open TCP connections for those HTTP connections will be forcefully closed if still not completed). - Any AWS SQS / AMQP handlers (decorated with

@aws_sns_sqsor@amqp) will stop receiving new messages. However handlers already processing a received message will be awaited to return their result. Unlike the HTTP handler connections there is no grace period for these queue consuming handlers. - Currently running scheduled handlers will also be awaited to fully complete their execution before the service will terminates. No new scheduled handlers will be started.

- When all HTTP connections are closed, all scheduled handlers has completed and all pub-sub handlers have been awaited, the service'

_stop_servicemethod is finally called (if implemented), where for example database connections can be closed. When the_stop_servicemethod returns (or immediately after completion of handler invocations if any_stop_serviceisn't implemented), the service will finally terminate.

It's recommended to use a http.termination_grace_period_seconds options value of around 30 seconds to allow for the graceful termination of HTTP connections. This value can be adjusted based on the expected time it takes for the service to complete the processing of incoming request.

Make sure that the orchestration engine (such as Kubernetes) waits at least 30 seconds from sending the SIGTERM to remove the pod. For extra compatibility when operating services in k8s and to get around most kind of edge-cases of intermittent timeouts and problems with ingress connections, (and unless your setup includes long running queue consuming handler calls which requires an even longer grace period), set the pod spec terminationGracePeriodSeconds to 90 seconds and use a preStop lifecycle hook of 20 seconds.

Keep the http.termination_grace_period_seconds options value lower than the pod spec's terminationGracePeriodSeconds value, as the latter is a hard limit for how long the pod will be allowed to run after receiving a SIGTERM signal.

In a setup where long running queue consuming handler calls commonly occurs, any grace period the orchestration engine uses will have to take that into account. It's generally advised to split work up into sizeable chunks that can quickly complete or if handlers are idempotent, apply the possibility to cancel long running handlers as part of the _stopping_service implementation.

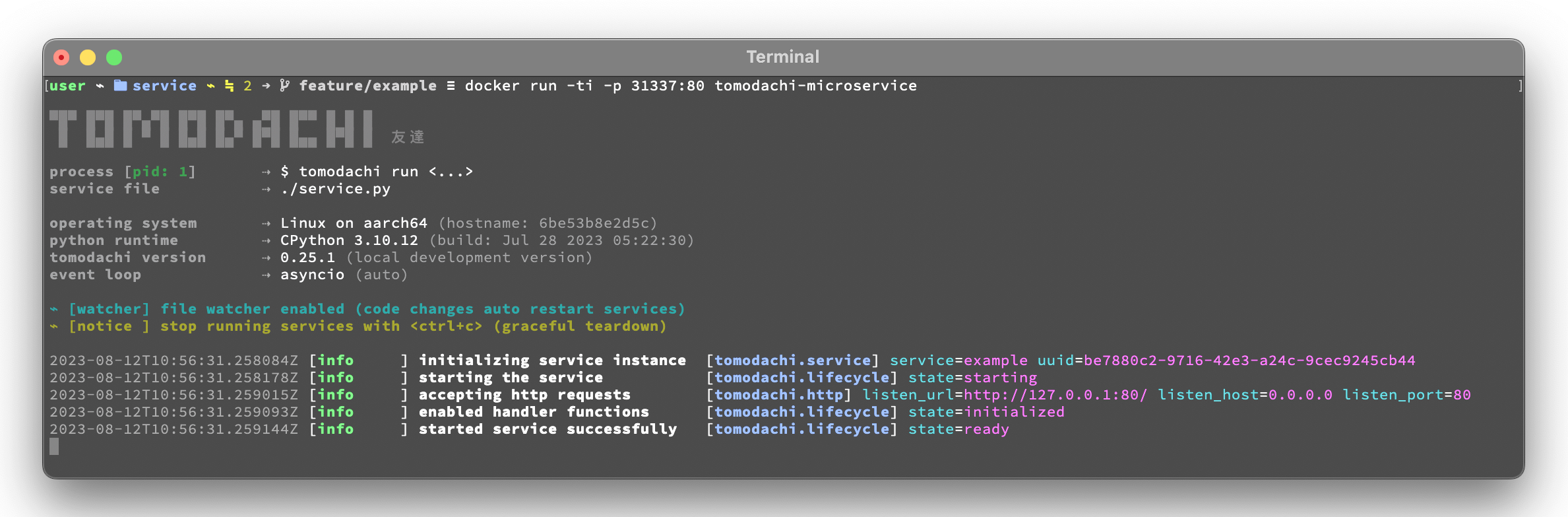

Example of a microservice containerized in Docker 🐳

A great way to distribute and operate microservices are usually to run

them in containers or even more interestingly, in clusters of compute

nodes. Here follows an example of getting a tomodachi based service up

and running in Docker.

We're building the service' container image using just two small

files, the Dockerfile and the actual code for the microservice,

service.py. In reality a service would probably not be quite this

small, but as a template to get started.

Dockerfile

FROM python:3.10-bullseye

RUN pip install tomodachi

RUN mkdir /app

WORKDIR /app

COPY service.py .

ENV PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1

CMD ["tomodachi", "run", "service.py"]service.py

import json

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "example"

options = tomodachi.Options(

http=tomodachi.Options.HTTP(

port=80,

content_type="application/json; charset=utf-8",

),

)

_healthy = True

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/")

async def index_endpoint(self, request):

# tomodachi.get_execution_context() can be used for

# debugging purposes or to add additional service context

# in logs or alerts.

execution_context = tomodachi.get_execution_context()

return json.dumps({

"data": "hello world!",

"execution_context": execution_context,

})

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/health/?", ignore_logging=True)

async def health_check(self, request):

if self._healthy:

return 200, json.dumps({"status": "healthy"})

else:

return 503, json.dumps({"status": "not healthy"})

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code=400)

async def error_400(self, request):

return json.dumps({"error": "bad-request"})

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code=404)

async def error_404(self, request):

return json.dumps({"error": "not-found"})

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code=405)

async def error_405(self, request):

return json.dumps({"error": "method-not-allowed"})Building and running the container, forwarding host's port 31337 to port 80

local ~/code/service$ docker build . -t tomodachi-microservice

# > Sending build context to Docker daemon 9.216kB

# > Step 1/7 : FROM python:3.10-bullseye

# > 3.10-bullseye: Pulling from library/python

# > ...

# > ---> 3f7f3ab065d4

# > Step 7/7 : CMD ["tomodachi", "run", "service.py"]

# > ---> Running in b8dfa9deb243

# > Removing intermediate container b8dfa9deb243

# > ---> 8f09a3614da3

# > Successfully built 8f09a3614da3

# > Successfully tagged tomodachi-microservice:latestlocal ~/code/service$ docker run -ti -p 31337:80 tomodachi-microserviceMaking requests to the running container

local ~$ curl http://127.0.0.1:31337/ | jq

# {

# "data": "hello world!",

# "execution_context": {

# "tomodachi_version": "x.x.xx",

# "python_version": "3.x.x",

# "system_platform": "Linux",

# "process_id": 1,

# "init_timestamp": "2022-10-16T13:38:01.201509Z",

# "event_loop": "asyncio",

# "http_enabled": true,

# "http_current_tasks": 1,

# "http_total_tasks": 1,

# "aiohttp_version": "x.x.xx"

# }

# }local ~$ curl http://127.0.0.1:31337/health -i

# > HTTP/1.1 200 OK

# > Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

# > Server: tomodachi

# > Content-Length: 21

# > Date: Sun, 16 Oct 2022 13:40:44 GMT

# >

# > {"status": "healthy"}local ~$ curl http://127.0.0.1:31337/no-route -i

# > HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

# > Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

# > Server: tomodachi

# > Content-Length: 22

# > Date: Sun, 16 Oct 2022 13:41:18 GMT

# >

# > {"error": "not-found"}It's actually as easy as that to get something spinning. The hard part is usually to figure out (or decide) what to build next.

Other popular ways of running microservices are of course to use them as

serverless functions, with an ability of scaling to zero (Lambda, Cloud

Functions, Knative, etc. may come to mind). Currently tomodachi works

best in a container setup and until proper serverless supporting

execution context is available in the library, it should be adviced to

hold off and use other tech for those kinds of deployments.

Available built-ins used as endpoints 🚀

As shown, there's different ways to trigger your microservice function in which the most common ones are either directly via HTTP or via event based messaging (for example AMQP or AWS SNS+SQS). Here's a list of the currently available built-ins you may use to decorate your service functions.

HTTP endpoints

@tomodachi.http

@tomodachi.http(method, url, ignore_logging=[200])

def handler(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

...Sets up an HTTP endpoint for the specified method (GET,

PUT, POST, DELETE) on the regexp url. Optionally specify

ignore_logging as a dict or tuple containing the status codes you

do not wish to log the access of.

Can also be set to True to

ignore everything except status code 500.

@tomodachi.http_static

@tomodachi.http_static(path, url)

def handler(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

# noop

passSets up an HTTP endpoint for static content available as GET

HEAD from the path on disk on the base regexp url.

@tomodachi.websocket

@tomodachi.websocket(url)

def handler(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

async def _receive(data: Union[str, bytes]) -> None:

...

async def _close() -> None:

...

return _receive, _closeSets up a websocket endpoint on the regexp url. The invoked

function is called upon websocket connection and should return a two

value tuple containing callables for a function receiving frames

(first callable) and a function called on websocket close (second

callable).

The passed arguments to the function beside the class

object is first the websocket response connection which can be

used to send frames to the client, and optionally also the request

object.

@tomodachi.http_error

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code)

def handler(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

...A function which will be called if the HTTP request would result

in a 4XX status_code. You may use this for example to set up a

custom handler on "404 Not Found" or "403 Forbidden" responses.

AWS SNS+SQS messaging

@tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs

@tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs(

topic=None,

competing=True,

queue_name=None,

filter_policy=FILTER_POLICY_DEFAULT,

visibility_timeout=VISIBILITY_TIMEOUT_DEFAULT,

dead_letter_queue_name=DEAD_LETTER_QUEUE_DEFAULT,

max_receive_count=MAX_RECEIVE_COUNT_DEFAULT,

fifo=False,

max_number_of_consumed_messages=MAX_NUMBER_OF_CONSUMED_MESSAGES

**kwargs,

)

def handler(self, data, *args, **kwargs):

...Topic and Queue

This would set up an AWS SQS queue, subscribing to messages on

the AWS SNS topic topic (if a topic is specified),

whereafter it will start consuming messages from the queue. The value

can be omitted in order to make the service consume messages from an existing

queue, without setting up an SNS topic subscription.

The competing value is used when the same queue name should be

used for several services of the same type and thus "compete" for

who should consume the message. Since tomodachi version 0.19.x

this value has a changed default value and will now default to

True as this is the most likely use-case for pub/sub in

distributed architectures.

Unless queue_name is specified an auto generated queue name will

be used. Additional prefixes to both topic and queue_name can be

assigned by setting the options.aws_sns_sqs.topic_prefix and

options.aws_sns_sqs.queue_name_prefix dict values.

FIFO queues + max number of consumed messages

AWS supports two types of queues and topics, namely standard and

FIFO. The major difference between these is that the latter

guarantees correct ordering and at-most-once delivery. By default,

tomodachi creates standard queues and topics. To create them as

FIFO instead, set fifo to True.

The max_number_of_consumed_messages setting determines how many

messages should be pulled from the queue at once. This is useful if

you have a resource-intensive task that you don't want other

messages to compete for. The default value is 10 for standard

queues and 1 for FIFO queues. The minimum value is 1, and the

maximum value is 10.

Filter policy

The filter_policy value of specified as a keyword argument will be

applied on the SNS subscription (for the specified topic and queue)

as the "FilterPolicy attribute. This will apply a filter on SNS

messages using the chosen "message attributes" and/or their values

specified in the filter. Make note that the filter policy dict

structure differs somewhat from the actual message attributes, as

values to the keys in the filter policy must be a dict (object) or

list (array).

Example: A filter policy value of

{"event": ["order_paid"], "currency": ["EUR", "USD"]} would set up

the SNS subscription to receive messages on the topic only where the

message attribute "event" is "order_paid" and the "currency"

value is either "EUR" or "USD".

If filter_policy is not specified as an argument (default), the

queue will receive messages on the topic as per already specified if

using an existing subscription, or receive all messages on the topic

if a new subscription is set up (default). Changing the

filter_policy on an existing subscription may take several minutes

to propagate.

Read more about the filter policy format on AWS:

Related to the above mentioned filter policy, the

tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs_publish (which is used for publishing

messages to SNS) and tomodachi.sqs_send_message (which sends

messages directly to SQS) functions, can specify "message

attributes" using the message_attributes keyword argument. Values

should be specified as a simple dict with keys and values.

Example: {"event": "order_paid", "paid_amount": 100, "currency": "EUR"}.

Visibility timeout

The visibility_timeout value will set the queue attribute

VisibilityTimeout if specified. To use already defined values for

a queue (default), do not supply any value to the

visibility_timeout keyword -- tomodachi will then not modify the

visibility timeout.

DLQ: Dead-letter queue

Similarly the values for dead_letter_queue_name in tandem with the

max_receive_count value will modify the queue attribute

RedrivePolicy in regards to the potential use of a dead-letter

queue to which messages will be delivered if they have been picked

up by consumers max_receive_count number of times but haven't

been deleted from the queue.

The value for dead_letter_queue_name

should either be a ARN for an SQS queue, which in that case requires

the queue to have been created in advance, or a alphanumeric queue

name, which in that case will be set up similar to the queue name

you specify in regards to prefixes, etc.

Both dead_letter_queue_name and max_receive_count needs to be

specified together, as they both affect the redrive policy. To

disable the use of DLQ, use a None value for the

dead_letter_queue_name keyword and the RedrivePolicy will be

removed from the queue attribute.

To use the already defined values

for a queue, do not supply any values to the keyword arguments in

the decorator. tomodachi will then not modify the queue attribute

and leave it as is.

Message envelope

Depending on the service message_envelope (previously named

message_protocol) attribute if used, parts of the enveloped data

would be distributed to different keyword arguments of the decorated

function. It's usually safe to just use data as an argument. You

can also specify a specific message_envelope value as a keyword

argument to the decorator for specifying a specific enveloping

method to use instead of the global one set for the service.

If you're utilizing from tomodachi.envelope import ProtobufBase

and using ProtobufBase as the specified service message_envelope

you may also pass a keyword argument proto_class into the

decorator, describing the protobuf (Protocol Buffers) generated

Python class to use for decoding incoming messages. Custom

enveloping classes can be built to fit your existing architecture or

for even more control of tracing and shared metadata between

services.

Encryption at rest via AWS KMS

Encryption at rest for AWS SNS and/or AWS SQS can optionally be

configured by specifying the KMS key alias or KMS key id as

tomodachi service options

options.aws_sns_sqs.sns_kms_master_key_id (to configure encryption

at rest on the SNS topics for which the tomodachi service handles

the SNS -> SQS subscriptions) and

options.aws_sns_sqs.sqs_kms_master_key_id (to configure encryption

at rest for the SQS queues which the service is consuming).

Note that an option value set to an empty string ("") or False will

unset the KMS master key id and thus disable encryption at rest. If

instead an option is completely unset or set to None value no

changes will be done to the KMS related attributes on an existing

topic or queue.

It's generally not advised to change the KMS master key id/alias values for resources currently in use.

If it's expected that the services themselves, via their IAM credentials or assumed role, are responsible for creating queues and topics, these options could be desirable to use.

Do not use these options if you instead are using IaC tooling to handle the topics, queues and subscriptions or that they for example are created / updated as a part of deployments.

See further details about AWS KMS for AWS SNS+SQS at:

- https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AWSSimpleQueueService/latest/SQSDeveloperGuide/sqs-server-side-encryption.html

- https://docs.aws.amazon.com/sns/latest/dg/sns-server-side-encryption.html#sse-key-terms.

AMQP messaging (RabbitMQ)

@tomodachi.amqp

@tomodachi.amqp(

routing_key,

exchange_name="amq.topic",

competing=True,

queue_name=None,

**kwargs,

)

def handler(self, data, *args, **kwargs):

...Routing key, Exchange and Queue

Sets up the method to be called whenever a AMQP / RabbitMQ message

is received for the specified routing_key. By default the

'amq.topic' topic exchange would be used, it may also be

overridden by setting the options.amqp.exchange_name dict value on

the service class.

The competing value is used when the same queue name should be

used for several services of the same type and thus "compete" for

who should consume the message. Since tomodachi version 0.19.x

this value has a changed default value and will now default to

True as this is the most likely use-case for pub/sub in

distributed architectures.

Unless queue_name is specified an auto generated queue name will

be used. Additional prefixes to both routing_key and queue_name

can be assigned by setting the options.amqp.routing_key_prefix and

options.amqp.queue_name_prefix dict values.

Message envelope

Depending on the service message_envelope (previously named

message_protocol) attribute if used, parts of the enveloped data

would be distributed to different keyword arguments of the decorated

function. It's usually safe to just use data as an argument. You

can also specify a specific message_envelope value as a keyword

argument to the decorator for specifying a specific enveloping

method to use instead of the global one set for the service.

If you're utilizing from tomodachi.envelope import ProtobufBase

and using ProtobufBase as the specified service message_envelope

you may also pass a keyword argument proto_class into the

decorator, describing the protobuf (Protocol Buffers) generated

Python class to use for decoding incoming messages. Custom

enveloping classes can be built to fit your existing architecture or

for even more control of tracing and shared metadata between

services.

Scheduled functions / cron / triggered on time interval

@tomodachi.schedule

@tomodachi.schedule(

interval=None,

timestamp=None,

timezone=None,

immediately=False,

)

def handler(self, *args, **kwargs):

...A scheduled function invoked on either a specified interval

(you may use the popular cron notation as a str for fine-grained

interval or specify an integer value of seconds) or a specific

timestamp. The timezone will default to your local time unless

explicitly stated.

When using an integer interval you may also specify wether the

function should be called immediately on service start or wait the

full interval seconds before its first invokation.

@tomodachi.heartbeat

@tomodachi.heartbeat

def handler(self, *args, **kwargs):

...A function which will be invoked every second.

@tomodachi.minutely / @tomodachi.hourly

@tomodachi.minutely

@tomodachi.hourly

@tomodachi.daily

@tomodachi.monthly

def handler(self, *args, **kwargs):

...A scheduled function which will be invoked once every minute / hour / day / month.

Scheduled tasks in distributed contexts

What is your use-case for scheduling function triggers or functions that trigger on an interval. These types of scheduling may not be optimal in clusters with many pods in the same replication set, as all the services running the same code will very likely execute at the same timestamp / interval (which in same cases may correlated with exactly when they were last deployed). As such these functions are quite naive and should only be used with some care, so that it triggering the functions several times doesn't incur unnecessary costs or come as a bad surprise if the functions aren't completely idempotent.

To perform a task on a specific timestamp or on an interval where only one of the available services of the same type in a cluster should trigger is a common thing to solve and there are several solutions to pick from., some kind of distributed consensus needs to be reached. Tooling exists, but what you need may differ depending on your use-case. There's algorithms for distributed consensus and leader election, Paxos or Raft, that luckily have already been implemented to solutions like the strongly consistent and distributed key-value stores etcd and TiKV.

Even primitive solutions

such as Redis SETNX commands would work, but could be costly or hard

to manage access levels around. If you're on k8s there's even a simple

"leader election" API available that just creates a 15 seconds lease.

Solutions are many and if you are in need, go hunting and find one that

suits your use-case, there's probably tooling and libraries available

to call it from your service functions.

Implementing proper consensus mechanisms and in turn leader election can be complicated. In distributed environments the architecture around these solutions needs to account for leases, decision making when consensus was not reached, how to handle crashed executors, quick recovery on master node(s) disruptions, etc.

To extend the functionality by building your own trigger decorators for

your endpoints, studying the built-in invoker classes should the first

step of action. All invoker classes should extend the class for a common

developer experience: tomodachi.invoker.Invoker.

Function signatures - keywords with transport centric values 🪄

Function handlers, middlewares and envelopes can specify additional keyword arguments in their signatures and receive transport centric values.

The following keywords can be used across all kind of handler functions, envelopes and envelopes parsing messages. These can be used to structure apps, logging, tracing, authentication, building more advanced messaging logic, etc.

AWS SNS+SQS related values - function signature keyword arguments

Use the following keywords arguments in function signatures (for handlers, middlewares and envelopes used for AWS SNS+SQS messages).

message_attributes |

Values specified as message attributes that accompanies the message body and that are among other things used for SNS queue subscription filter policies and for distributed tracing. |

queue_url |

Can be used to modify visibility of messages, provide exponential backoffs, move to DLQs, etc. |

receipt_handle |

Can be used to modify visibility of messages, provide exponential backoffs, move to DLQs, etc. |

approximate_receive_count |

A value that specifies approximately how many times this message has been received from consumers on SQS.ReceiveMessage calls. Handlers that received a message, but that doesn't delete it from the queue (for example in order to make it visible for other consumers or in case of errors), will add to this count for each time they received it. |

topic |

Simply the name of the SNS topic. For messages sent directly to the queue (for example via SQS.SendMessage API calls), instead of via SNS topic subscriptions (SNS.Publish), the value of topic will be an empty string. |

sns_message_id |

The message identifier for the SNS message (which is usually embedded in the body of a SQS message). Ths SNS message identifier is the same that is returned in the response when publishing a message with SNS.Publish. The sns_message_id is read from within the "Body" of SQS messages, if the message body contains a message that comes from an SNS topic subscription. If the SQS message doesn't originate from SNS (if the message isn't type "Notification", and holds a "TopicArn" value), then sns_message_id will result in an empty string. |

sqs_message_id |

The SQS message identifier, which naturally will differ from the SNS message identifier as one SNS message can be propagated to several SQS queues. The sqs_message_id is read from the "MessageId" value in the top of the SQS message. |

message_type |

Returns the "Type" value from the message body. For messages consumed from a queue that was sent there from an SNS topic, the message_type will be "Notification". |

raw_message_body |

Returns the full contents (as a string) from "Body", which can be used to implement custom listeners, tailored for more advanced workflows, where more flexibility is needed. |

message_timestamp |

A timestamp of when the original SNS message was published. |

message_deduplication_id |

The deduplication id for messages in FIFO queues (or None on messages in non-FIFO queues). |

message_group_id |

The group id for messages in FIFO queues (orNone on messages in non-FIFO queues). |

HTTP related values - function signature keyword arguments

Use the following keywords arguments in function signatures (for handlers and middlewares used for HTTP requests).

request |

The aiohttp request object which holds functionality for all things HTTP requests. |

status_code |

Specified when predefined error handlers are run. Using the keyword in handlers and middlewares for requests not invoking error handlers should preferably be specified with a default value to ensure it will work on both error handlers and request router handlers. |

websocket |

Will be added to websocket requests if used. |

Middlewares for HTTP and messaging (AWS SNS+SQS, AMQP, etc.) 🧱

Middlewares can be used to add functionality to the service, for example to add logging, authentication, tracing, build more advanced logic for messaging, unpack request queries, modify HTTP responses, handle uncaught errors, add additional context to handlers, etc.

Custom middleware functions or objects that can be called are added to

the service by specifying them as a list in the http_middleware and

message_middleware attribute of the service class.

from .middleware import logger_middleware

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "middleware-example"

http_middleware = [logger_middleware]

...Middlewares are invoked as a stack in the order they are specified in

http_middleware or message_middleware with the first callable in the

list to be called first (and then also return last).

Provided arguments to middleware functions

- The first unbound argument of a middleware function will receive the

coroutine function to call next (which would be either the handlers

function or a function for the next middleware in the chain).

(recommended name:

func) - (optional) The second unbound argument of a middleware function will

receive the service class object. (recommended name:

service) - (optional) The third unbound argument of a middleware function will

receive the

requestobject for HTTP middlewares, or themessage(as parsed by the envelope) for message middlewares. (recommended name:requestormessage)

Use the recommended names to prevent collisions with passed keywords for transport centric values that are also sent to the middleware if the keyword arguments are defined in the function signature.

Calling the handler or the next middleware in the chain

When calling the next function in the chain, the middleware function

should be called as an awaitable function (await func()) and for HTTP

middlewares the result should most commonly be returned.

Adding custom arguments passed on to the handler

The function can be called with any number of custom keyword arguments, which will then be passed to each following middleware and the handler itself. This pattern works a bit how contextvars can be set up, but could be useful for passing values and objects instead of keeping them in a global context.

async def logger_middleware(func: Callable[..., Awaitable], *, traceid: str = "") -> Any:

if not traceid:

traceid = uuid.uuid4().hex

logger = Logger(traceid=traceid)

# Passes the logger and traceid to following middlewares and to the handler

return await func(logger=logger, traceid=traceid)A middleware can only add new keywords or modify the values or existing keyword arguments (by passing it through again with the new value). The exception to this is that passed keywords for transport centric values will be ignored - their value cannot be modified - they will retain their original value.

While a middleware can modify the values of custom keyword arguments, there is no way for a middleware to completely remove any keyword that has been added by previous middlewares.

Example of a middleware specified as a function that adds tracing to AWS SQS handlers:

This example portrays a middleware function which adds trace spans around the function, with the trace context populated from a "traceparent header" value collected from a SNS message' message attribute. The topic name and SNS message identifier is also added as attributes to the trace span.

async def trace_middleware(

func: Callable[..., Awaitable],

*,

queue_url: str,

topic: str,

message_attributes: dict,

sns_message_id: str,

sqs_message_id: str,

) -> None:

ctx = TraceContextTextMapPropagator().extract(carrier=message_attributes)

with tracer.start_as_current_span(f"SNSSQS handler '{func.__name__}'", context=ctx) as span:

span.set_attribute("messaging.system", "aws_sqs")

span.set_attribute("messaging.operation", "process")

span.set_attribute("messaging.destination.name", queue_url.rsplit("/")[-1])

span.set_attribute("messaging.destination_publish.name", topic or queue_url.rsplit("/")[-1])

span.set_attribute("messaging.message.id", sns_message_id or sqs_message_id)

try:

# Calls the handler function (or next middleware in the chain)

await func()

except BaseException as exc:

logging.getLogger("exception").exception(exc)

span.record_exception(exc, escaped=True)

span.set_status(StatusCode.ERROR, f"{exc.__class__.__name__}: {exc}")

raise excfrom .middleware import trace_middleware

from .envelope import Event, MessageEnvelope

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "middleware-example"

message_envelope: MessageEnvelope(key="event")

message_middleware = [trace_middleware]

@tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs("example-topic", queue_name="example-queue")

async def handler(self, event: Event) -> None:

...Example of a middleware specified as a class:

A middleware can also be specified as the object of a class, in which

case the __call__ method of the object will be invoked as the

middleware function. Note that bound functions such as self has to be

included in the signature as it's called as a normal class function.

This class provides a simplistic basic auth implementation validating credentials in the HTTP Authorization header for HTTP requests to the service.

class BasicAuthMiddleware:

def __init__(self, username: str, password: str) -> None:

self.valid_credentials = base64.b64encode(f"{username}:{password}".encode()).decode()

async def __call__(

self,

func: Callable[..., Awaitable[web.Response]],

*,

request: web.Request,

) -> web.Response:

try:

auth = request.headers.get("Authorization", "")

encoded_credentials = auth.split()[-1] if auth.startswith("Basic ") else ""

if encoded_credentials == self.valid_credentials:

username = base64.b64decode(encoded_credentials).decode().split(":")[0]

# Calls the handler function (or next middleware in the chain).

# The handler (and following middlewares) can use username in their signature.

return await func(username=username)

elif auth:

return web.json_response({"status": "bad credentials"}, status=401)

return web.json_response({"status": "auth required"}, status=401)

except BaseException as exc:

try:

logging.getLogger("exception").exception(exc)

raise exc

finally:

return web.json_response({"status": "internal server error"}, status=500)from .middleware import trace_middleware

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "middleware-example"

http_middleware = [BasicAuthMiddleware(username="example", password="example")]

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/")

async def handler(self, request: web.Request, username: str) -> web.Response:

...

Logging and log formatting using the tomodachi.logging module 📚

A context aware logger is available from the tomodachi.logging module

that can be fetched with tomodachi.logging.get_logger() or just

tomodachi.get_logger() for short.

The logger is a initiated using the popular structlog package

(structlog

documentation),

and can be used in the same way as the standard library logger, with a

few additional features, such as holding a context and logging of

additional values.

The logger returned from tomodachi.get_logger() will hold the context

of the current handler task or request for rich contextual log records.

To get a logger with another name than the logger set for the current

context, use tomodachi.get_logger(name="my-logger").

from typing import Any

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "service"

@tomodachi.aws_sns_sqs("test-topic", queue_name="test-queue")

async def sqs_handler(self, data: Any, topic: str, sns_message_id: str) -> None:

tomodachi.get_logger().info("received msg", topic=topic, sns_message_id=sns_message_id)The log record will be enriched with the context of the current handler

task or request and the output should look something like this if the

json formatter is used (note that the example output below has been

prettified -- the JSON that is actually used outputs the entire log

entry on one single line):

{

"timestamp": "2023-08-13T17:44:09.176295Z",

"logger": "tomodachi.awssnssqs.handler",

"level": "info",

"message": "received msg",

"handler": "sqs_handler",

"type": "tomodachi.awssnssqs",

"topic": "test-topic",

"sns_message_id": "a1eba63e-8772-4b36-b7e0-b2f524f34bff"

}

Interactions with Python's built-in logging module

Note that the log entries are propagated to the standard library logger (as long as it wasn't filtered), in order to allow third party handler hooks to pick up records or act on them. This will make sure that integrations such a Sentry's exception tracing will work out of the box.

Similarly the tomodachi logger will also by default receive records

from the standard library logger as adds a logging.root handler, so

that the tomodachi logger can be used as a drop-in replacement for the

standard library logger. Because of this third party modules using

Python's default logging module will use the same formatter as

tomodachi. Note that if logging.basicConfig() is called before the

tomodachi logger is initialized, tomodachi may not be able to add

its logging.root handler.

Note that when using the standard library logger directly the contextual logger won't be selected by default.

import logging

from aiohttp.web import Request, Response

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "service"

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/example")

async def http_handler(self, request: Request) -> Response:

# contextual logger

tomodachi.get_logger().info("http request")

# these two rows result in similar log records

logging.getLogger("service.logger").info("with logging module")

tomodachi.get_logger("service.logger").info("with tomodachi.logging module")

# extra fields from built in logger ends up as "extra" in log records

logging.getLogger("service.logger").info("adding extra", extra={

"http_request_path": request.path

})

return Response(body="hello world")A GET request to /example of this service would result in five log

records being emitted (as shown formatted with the json formatter).

The four from the example above and the last one from the

tomodachi.transport.http module.

{"timestamp": "2023-08-13T19:25:15.923627Z", "logger": "tomodachi.http.handler", "level": "info", "message": "http request", "handler": "http_handler", "type": "tomodachi.http"}

{"timestamp": "2023-08-13T19:25:15.923894Z", "logger": "service.logger", "level": "info", "message": "with logging module"}

{"timestamp": "2023-08-13T19:25:15.924043Z", "logger": "service.logger", "level": "info", "message": "with tomodachi.logging module"}

{"timestamp": "2023-08-13T19:25:15.924172Z", "logger": "service.logger", "level": "info", "message": "adding extra", "extra": {"http_request_path": "/example"}}

{"timestamp": "2023-08-13T19:25:15.924507Z", "logger": "tomodachi.http.response", "level": "info", "message": "", "status_code": 200, "remote_ip": "127.0.0.1", "request_method": "GET", "request_path": "/example", "http_version": "HTTP/1.1", "response_content_length": 11, "user_agent": "curl/7.88.1", "handler_elapsed_time": "0.00135s", "request_time": "0.00143s"}Configuring the logger

Start the service using the --logger json arguments (or setting

TOMODACHI_LOGGER=json environment value) to change the log formatter

to use the json log formatter. The default log formatter console is

mostly suited for local development environments as it provides a

structured and colorized view of log records.

It's also possible to use your own logger implementation by specifying

--custom-logger ... (or setting TOMODACHI_CUSTOM_LOGGER=...

environment value).

Read more about how to start the service with another formatter or implementation in the usage section

Using OpenTelemetry instrumentation

Install tomodachi using the opentelemetry extras to enable

instrumentation for OpenTelemetry. In addition, install with the

opentelemetry-exporter-prometheus extras to use Prometheus exporter

metrics.

local ~$ pip install tomodachi[opentelemetry]

local ~$ pip install tomodachi[opentelemetry,opentelemetry-exporter-prometheus]When added as a Poetry dependency the opentelemetry extras can be

enabled by adding tomodachi = {extras = ["opentelemetry"]} to the

pyproject.toml file, and when added to a requiements.txt file the

opentelemetry extras can be enabled by adding

tomodachi[opentelemetry] to the file.

Auto instrumentation: tomodachi --opentelemetry-instrument

Passing the --opentelemetry-instrument argument to tomodachi run

will automatically instrument the service with the appropriate exporters

and configuration according to the set OTEL_* environment variables.

If tomodachi is installed in the environment, using

tomodachi --opentelemetry-instrument service.py is mostly equivalent

to running opentelemetry-instrument tomodachi run service.py and will

load distros, configurators and instrumentors automatically in the same

way as the opentelemetry-instrument CLI would do.

local ~$ OTEL_LOGS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_TRACES_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_METRICS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_SERVICE_NAME=example-service \

tomodachi --opentelemetry-instrument run service/app.pyThe environment variable TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT if set

will also enable auto instrumentation in the same way.

local ~$ OTEL_LOGS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_TRACES_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_METRICS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_SERVICE_NAME=example-service \

TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT=1 \

tomodachi run service/app.py

Auto instrumentation using the opentelemetry-instrument CLI

Auto instrumentation using the opentelemetry-instrument CLI can be

achieved by starting services using

opentelemetry-instrument [otel-options] tomodachi run [options] <service.py ...>.

# either define the OTEL_* environment variables to specify instrumentation specification

local ~$ OTEL_LOGS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_TRACES_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_METRICS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_SERVICE_NAME=example-service \

opentelemetry-instrument tomodachi run service/app.py

# or use the arguments passed to the opentelemetry-instrument command

local ~$ opentelemetry-instrument \

--logs_exporter console \

--traces_exporter console \

--metrics_exporter console \

--service_name example-service \

tomodachi run service/app.pyManual instrumentation

Auto instrumentation using either

tomodachi --opentelemetry-instrument, setting the

TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT=1 env value or using the

opentelemetry-instrument CLI are the recommended ways of instrumenting

services, as they will automatically instrument the service (and libs

with instrumentors installed) with the appropriate exporters and

configuration.

However, instrumentation can also be enabled by importing the

TomodachiInstrumentor instrumentation class and calling its'

instrument function.

import tomodachi

from tomodachi.opentelemetry import TomodachiInstrumentor

TomodachiInstrumentor().instrument()

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "example-service"

@tomodachi.http(GET, r"/example")

async def example(self, request):

return 200, "hello world"Starting such a service with the appropriate OTEL_* environment

variables would properly instrument traces, logs and metrics for the

service without the need to use the opentelemetry-instrument CLI.

local ~$ OTEL_LOGS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_TRACES_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_METRICS_EXPORTER=console \

OTEL_SERVICE_NAME=example-service \

tomodachi run service/app.py

Service name dynamically set if missing OTEL_SERVICE_NAME value

If the OTEL_SERVICE_NAME environment variable value (or

--service_name argument to opentelemetry-instrument) is not set, the

resource' service.name will instead be set to the name attribute of

the service class. In case the service class uses the default generic

names (service or app), the resource' service.name will instead

be set to the default as specified in

https://github.com/open-telemetry/semantic-conventions/tree/main/docs/resource#service.

In the rare case where there's multiple tomodachi services started

within the same Python process, it should be noted that OTEL traces,

metrics and logging will primarily use the OTEL_SERVICE_NAME, and if

it's missing then use the name from the first instrumented service

class. The same goes for the service.instance.id resource attribute,

which will be set to the first instrumented service class' uuid value

(which in most cases is automatically assigned on service start).

Multi-service execution won't accurately distinguish the service name

of tracers, meters and loggers. The recommended solution if this is an

issue, is to split the services into separate processes instead.

Exclude lists to exclude certain URLs from traces and metrics

To exclude certain URLs from traces and metrics, set the environment

variable OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_EXCLUDED_URLS (or

OTEL_PYTHON_EXCLUDED_URLS to cover all instrumentations) to a string

of comma delimited regexes that match the URLs.

Regexes from the OTEL_PYTHON_AIOHTTP_EXCLUDED_URLS environment

variable will also be excluded.

For example,

export OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_EXCLUDED_URLS="client/.*/info,healthcheck"will exclude requests such as https://site/client/123/info and

https://site/xyz/healthcheck.

You can also pass comma delimited regexes directly to the instrument

method:

TomodachiInstrumentor().instrument(excluded_urls="client/.*/info,healthcheck")Prometheus meter provider (experimental)

The tomodachi.opentelemetry module also provides a Prometheus meter

provider that can be used to export metrics to Prometheus. Run

opentelemetry-instrument with the

--meter_provider tomodachi_prometheus argument (or set

OTEL_PYTHON_METER_PROVIDER=tomodachi_prometheus environment value) to

enable the Prometheus meter provider.

Environment variables to configure Prometheus meter provider

-

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_ADDRESSspecifies the host address the Prometheus export server should listen on. (default:"localhost") -

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_PORTspecifies the port the Prometheus export server should listen on. (default:9464) -

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_INCLUDE_SCOPE_INFOspecifies whether to include scope information asotel_scope_infovalue. (default:true) -

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_INCLUDE_TARGET_INFOspecifies whether to include resource attributes astarget_infovalue. (default:true) -

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_EXEMPLARS_ENABLEDspecifies whether exemplars (experimental) should be collected and used in Prometheus export. (default:false) -

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_NAMESPACE_PREFIXspecifies the namespace prefix for Prometheus metrics. A final underscore is automatically added if prefix is used. (default:"")

Dependency requirement for Prometheus meter provider

The tomodachi_prometheus meter provider requires that the

opentelemetry-exporter-prometheusand prometheus_client packages

package are installed.

Use tomodachi extras opentelemetry-exporter-prometheus to

automatically include a compatible version of the exporter.

OpenMetrics output from Prometheus with exemplars enabled

With exemplars enabled, make sure to call the Prometheus client with the

accept header application/openmetrics-text to ensure exemplars are

included in the response.

curl http://localhost:9464/metrics -H "Accept: application/openmetrics-text"💡 Note that if the accept header application/openmetrics-text is

missing from the request, exemplars will be excluded from the response.

Example: starting a service with instrumentation

This example will start and instrument a service with OTLP exported

traces sent to the endpoint otelcol:4317 and metrics that can be

scraped by Prometheus from port 9464. All metrics except for

target_info and otel_scope_info will be prefixed with

"tomodachi_". Additionally exemplars will be added to the Prometheus

collected metrics that includes sample exemplars with trace_id and

span_id labels.

local ~$ TOMODACHI_OPENTELEMETRY_INSTRUMENT=1 \

OTEL_TRACES_EXPORTER=otlp \

OTEL_EXPORTER_OTLP_ENDPOINT=otelcol:4317 \

OTEL_PYTHON_METER_PROVIDER=tomodachi_prometheus \

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_EXEMPLARS_ENABLED=true \

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_ADDRESS=0.0.0.0 \

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_PORT=9464 \

OTEL_PYTHON_TOMODACHI_PROMETHEUS_NAMESPACE_PREFIX=tomodachi \

tomodachi run service/app.pyAdditional configuration options 🤩

In the service class an attribute named options (as a

tomodachi.Options object) can be set for additional configuration.

import json

import tomodachi

class Service(tomodachi.Service):

name = "http-example"

options = tomodachi.Options(

http=tomodachi.Options.HTTP(

port=80,

content_type="application/json; charset=utf-8",

real_ip_from=[

"127.0.0.1/32",

"10.0.0.0/8",

"172.16.0.0/12",

"192.168.0.0/16",

],

keepalive_timeout=5,

max_keepalive_requests=20,

),

watcher=tomodachi.Options.Watcher(

ignored_dirs=["node_modules"],

),

)

@tomodachi.http("GET", r"/health")

async def health_check(self, request):

return 200, json.dumps({"status": "healthy"})

# Specify custom 404 catch-all response

@tomodachi.http_error(status_code=404)

async def error_404(self, request):

return json.dumps({"error": "not-found"})

Options are read or written via the service' options attribute

A service option can be accessed via the configuration key in numerous ways.

-

options.http.sub_key(example:options.http.port) -

options[f"http.{sub_key}"](example:options["http.port"]) -

options["http"][sub_key](example:options["http"]["port"])

The service options attribute is an object of tomodachi.Options type.

HTTP server parameters

| Configuration key | Description | Default |

|---|---|---|

http.port |

TCP port (integer value) to listen for incoming connections. | 9700 |

http.host |

Network interface to bind TCP server to. "0.0.0.0" will bind to all IPv4 interfaces. None or "" will assume all network interfaces. |

"0.0.0.0" |

http.reuse_port |

If set to True (which is also the default value on Linux) the HTTP server will bind to the port using the socket option SO_REUSEPORT. This will allow several processes to bind to the same port, which could be useful when running services via a process manager such as supervisord or when it's desired to run several processes of a service to utilize additional CPU cores, etc. Note that the reuse_port option cannot be used on non-Linux platforms. |

True on Linux, otherwise False

|

http.keepalive_timeout |

Enables connections to use keep-alive if set to an integer value over 0. Number of seconds to keep idle incoming connections open. |

0 |

http.max_keepalive_requests |

An optional number (int) of requests which is allowed for a keep-alive connection. After the specified number of requests has been done, the connection will be closed. An option value of 0 or None (default) will allow any number of requests over an open keep-alive connection. |

None |

http.max_keepalive_time |

An optional maximum time in seconds (int) for which keep-alive connections are kept open. If a keep-alive connection has been kept open for more than http.max_keepalive_time seconds, the following request will be closed upon returning a response. The feature is not used by default and won't be used if the value is 0 or None. A keep-alive connection may otherwise be open unless inactive for more than the keep-alive timeout. |

None |

http.client_max_size |

The client’s maximum size in a request, as an integer, in bytes. | (1024 ** 2) * 100 |

http.termination_grace_period_seconds |

The number of seconds to wait for functions called via HTTP to gracefully finish execution before terminating the service, for example if service received a SIGINT or SIGTERM signal while requests were still awaiting response results. |

30 |

http.real_ip_header |

Header to read the value of the client's real IP address from if service operates behind a reverse proxy. Only used if http.real_ip_from is set and the proxy's IP correlates with the value from http.real_ip_from. |

"X-Forwarded-For" |

http.real_ip_from |

IP address(es) or IP subnet(s) / CIDR. Allows the http.real_ip_header header value to be used as client's IP address if connecting reverse proxy's IP equals a value in the list or is within a specified subnet. For example ["127.0.0.1/32", "10.0.0.0/8", "172.16.0.0/12", "192.168.0.0/16"] would permit header to be used if closest reverse proxy is "127.0.0.1" or within the three common private network IP address ranges. |

[] |

http.content_type |

Default content-type header to use if not specified in the response. | "text/plain; charset=utf-8" |

http.access_log |

If set to the default value (boolean) True the HTTP access log will be output to stdout (logger tomodachi.http). If set to a str value, the access log will additionally also be stored to file using value as filename. |

True |

http.server_header |

"Server" header value in responses. |

"tomodachi" |

AWS SNS+SQS credentials and prefixes

| Configuration key | Description | Default |

|---|---|---|

aws_sns_sqs.region_name |

The AWS region to use for SNS+SQS pub/sub API requests. | None |

aws_sns_sqs.aws_access_key_id |

The AWS access key to use for SNS+SQS pub/sub API requests. | None |

aws_sns_sqs.aws_secret_access_key |